News

Scores of Boko Haram terrorists killed in Borno ambush

Scores of Boko Haram terrorists killed in Borno ambush

…… As security forces also sustained casualties

By: Ndahi Marama

Dozens of Terrorists suspected to be members of Boko Haram/ISWAP have been killed in an ambush on troops of 21 Armoured Brigade along Bama-Kashimri village in Bama Local Government Area of Borno State.

The troops according to Credible Military Source revealed that they were on clearance operations around the Kashimri general area when the incident took place last Friday (Yesterday).

The Source said, troops of the Joint Task Force North East ‘ Operation Hadin Kai’ responded swiftly with firepower, as over 30 terrorists were neutralized, while others fled with gunshot wounds.

He said, unfortunately, the Officer who led the clearance operation (Names withheld), with some soldiers, two members of Civilian Joint Task Force and two Vigilantes paid the supreme price during the encounter.

“Yes, out troops came under Boko Haram ambush along Bama- Kashimri village last Friday while on clearance operations.

“Troops responded swiftly and nuetralized dozens of the terrorists, as scores fled with gunshot wounds.

” Unfortunately, the Officer who led the clearance operation (Names withheld), with some soldiers, two members of Civilian Joint Task Force and two Vigilantes paid the supreme price during the encounter”. The Military Source revealed.

He however said, the troops have sustained high spirit, as further operations are ongoing in all fronts to maintain pressure on the terrorists and deny them freedom of movement.

Scores of Boko Haram terrorists killed in Borno ambush

News

European Union Commits €22m to Accelerate Nigeria’s Fibre Network Under BRIDGE Project

European Union Commits €22m to Accelerate Nigeria’s Fibre Network Under BRIDGE Project

By: Michael Mike

The European Union has pledged €22 million in grant funding to support Nigeria’s large-scale fibre-optic expansion, reinforcing the Federal Government’s drive to transform the country’s digital backbone.

The grant, announced in Abuja on Wednesday, will be channelled through the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) and on-granted to the Federal Ministry of Communications, Innovation and Digital Economy for implementation of the government’s Project BRIDGE initiative.

The EU funding will sit alongside an €86 million loan from the EBRD’s own resources, pending final approval. The operation represents the EBRD’s first major sovereign financing in Nigeria since the country formally became a shareholder of the bank last year.

Minister of Communications, Innovation and Digital Economy, Bosun Tijjani described the agreement as a decisive step toward delivering the BRIDGE project within schedule, noting that Nigeria’s digital transformation agenda depends heavily on robust and inclusive broadband infrastructure.

He said the partnership reflects growing confidence in Nigeria’s digital roadmap and expressed optimism that 2026 would mark a year of tangible progress in cooperation between Nigeria and the EU.

EBRD President, Odile Renaud-Basso, who is on an official visit to Nigeria, said the bank was proud to collaborate with the EU to expand digital infrastructure in Africa’s largest economy. She noted that the technical cooperation embedded in the financing is structured to crowd in private capital while ensuring secure, resilient and inclusive connectivity.

EU Ambassador to Nigeria, Gautier Mignot, underscored the strategic importance of digital networks to both Nigeria and the EU, stressing the need for trusted, high-integrity infrastructure built to international standards.

Project BRIDGE aims to deploy 90,000 kilometres of fibre-optic cables nationwide through a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) that will be capitalised with sovereign loans and private sector participation. In addition to the EBRD financing, the Federal Government is expected to receive support from the World Bank and the African Development Bank.

The EU’s €22 million package combines technical assistance with investment support to speed up project preparation and strengthen implementation capacity. It will fund low-level design work for about 40,000 kilometres of the planned network, including route mapping, crossing surveys, digital planning, quality assurance and security risk assessments aligned with global best practices.

Officials said this groundwork would provide the SPV with a ready-to-execute blueprint, enabling immediate rollout once financing arrangements are finalised and the vehicle is established with at least 51 per cent private sector ownership.

Beyond infrastructure, the grant is expected to deepen Nigeria’s digital skills base. About 2,000 technicians will receive specialised training, while small subcontractors will gain access to pooled procurement systems and equipment subsidies designed to reduce entry barriers.

Authorities estimate that these measures could lower deployment costs by between 20 and 30 per cent, while promoting adherence to Nigerian and EU quality standards and encouraging participation of European technology suppliers in the fibre supply chain.

The intervention forms part of the EU’s broader Global Gateway strategy, which supports investments in digital infrastructure, public services and human capital development across partner countries.

For Nigeria, the partnership signals renewed international backing for its ambition to build a resilient, open-access broadband network capable of driving economic growth, innovation and digital inclusion nationwide.

European Union Commits €22m to Accelerate Nigeria’s Fibre Network Under BRIDGE Project

News

Troops repel insurgents, neutralise suspected informant in Borno

Troops repel insurgents, neutralise suspected informant in Borno

By: Zagazola Makama

Troops of Operation Hadin Kai have repelled suspected insurgents and neutralised a suspected informant during operations in Ngamdu area of Borno.

Military sources said the action followed signals intelligence indicating that suspected Boko Haram elements were massing.

At about 2:30 a.m. on Feb. 18, troops carried out a fire mission on the identified area, forcing the insurgents to disperse and abort their suspected plan.

Shortly afterward, at about 3:45 a.m., troops engaged and neutralised a suspected insurgent informant who attempted to breach the trench defensive position in Ngamdu.

Sources said the troops immediately conducted a search of the surrounding area after the encounter but made no further contact with fleeing suspects.

Troops repel insurgents, neutralise suspected informant in Borno

News

Yobe: Troops Disperse Terrorists, Arrest Five Suspected Arms Smugglers

Yobe: Troops Disperse Terrorists, Arrest Five Suspected Arms Smugglers

By: Zagazola Makama

Troops of Operation Hadin Kai have disrupted a suspected terrorist gathering and arrested five suspected arms smugglers during separate operations in Yobe State.

Security sources said that at about 6:21 p.m. on Feb. 17, troops conducted a fire mission following credible intelligence that terrorists were converging in large numbers on motorcycles at Mangari, about 10.6 kilometres from the location of the 135 Special Forces Battalion in Buratai.

The swift action forced the insurgents to disperse in disarray, effectively disrupting their suspected plans.

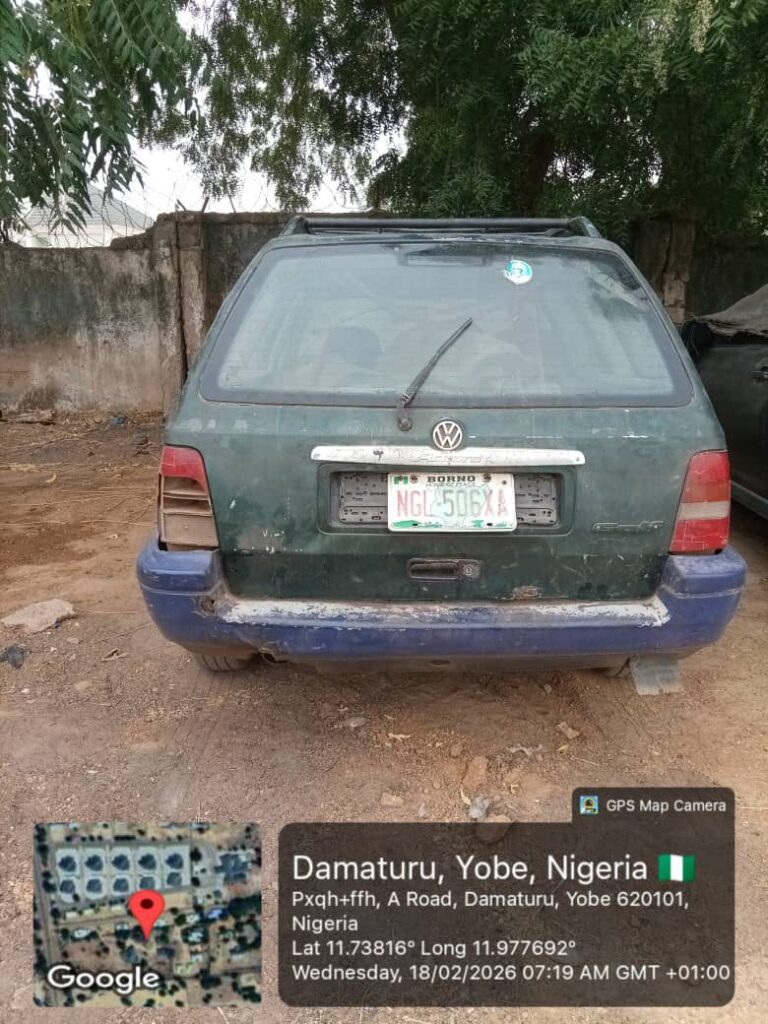

In a separate development, troops of the Forward Operating Base (FOB) Potiskum apprehended five suspected arms smugglers and abductors at about 4:30 a.m. on Feb. 18 at a checkpoint along the Gombe–Potiskum road.

Those arrested included a 41-year-old suspect, Baba Abare, who was found in possession of an AK-47 rifle, alongside four others identified as Idris Zakari, 33; Nasiru Aliyu, 25; Abdullahi Sulaiman, 35; and Mohammed Idris, 34, all said to be indigenes of Potiskum town.

The suspects were intercepted in two Golf Wagon vehicles bearing registration numbers Borno NGL-506XA and Kaduna DKD16-01.

They were disarmed and handed over to appropriate authorities for further investigation.

Yobe: Troops Disperse Terrorists, Arrest Five Suspected Arms Smugglers

-

News2 years ago

News2 years agoRoger Federer’s Shock as DNA Results Reveal Myla and Charlene Are Not His Biological Children

-

Opinions4 years ago

Opinions4 years agoTHE PLIGHT OF FARIDA

-

News10 months ago

News10 months agoFAILED COUP IN BURKINA FASO: HOW TRAORÉ NARROWLY ESCAPED ASSASSINATION PLOT AMID FOREIGN INTERFERENCE CLAIMS

-

News2 years ago

News2 years agoEYN: Rev. Billi, Distortion of History, and The Living Tamarind Tree

-

Opinions4 years ago

Opinions4 years agoPOLICE CHARGE ROOMS, A MINTING PRESS

-

ACADEMICS2 years ago

ACADEMICS2 years agoA History of Biu” (2015) and The Lingering Bura-Pabir Question (1)

-

Columns2 years ago

Columns2 years agoArmy University Biu: There is certain interest, but certainly not from Borno.

-

Opinions2 years ago

Opinions2 years agoTinubu,Shettima: The epidemic of economic, insecurity in Nigeria