Feature

Features: Two years after the ajaokuta ban in Borno, insurgents and residents now scavenge for plastics and firewood

Features: Two years after the ajaokuta ban in Borno, insurgents and residents now scavenge for plastics and firewood

By: Bodunrin Kayode

“Ajaokuta” is the name of a council area in kogi state. But that is for those not living in north Eastern Nigeria. In North Eastern Nigeria, “Ajaokuta” is used to mean scrap metals both in kanuri and hausa. As a result any metallic material not useful like empty “can of soft drinks” or beer which can be turned into money by making aluminum pots or containers. Anything not usable again and condemned to the metal bin made from iron or aluminium is big money to both the boko haram insurgents and the residents who search for them as relics of war.

The scavenging for these scrapes however soon woke up the recycling industry which had been restricted to mostly can drinks before the advent of the war. So many vehicles, military and civilians which were abandoned in the bush where it got broken down and became impossible to tow out before the insurgents took over 21 council areas became ready scrap metals inside the savannah. Because nobody in his right senses will spend more than ten minutes inside insurgents territory without being killed during the peak of the crisis.

This was how ajaokuta became a reality in north east Nigeria and such scraps became money in the hands of these scavengers on both sides of the divide who knew its value. These desperate scavengers of scrap materials turned even discarded car parts in organized garages to big money. And it is for that instant cash that some internally displaced people (IDPs) decided to be making fast money from it 6. This is because most of them are confined to the Head Quarters of their council areas unable to farm and fish or make a living for themselves where necessary.

With the shut down of organized idp camps in the city of Maiduguri these residents these days are becoming restless since they can’t earn their living through farming which is their primary past times. They hardly sit down where they are confined in the hinterlands sub camps pending the end of the war. This is because most of them disregard the war situation that has been declared in the north east and insist on wanting to live normal lives while still surrounded by insurgents. Some entered the maiduguri idp camps years ago without a family and now they are back to their council area sub camps with many wives and children. And they don’t see why the Governor, Babagana Zulum was complaining recently about that.

Borno State has witnessed several skirmishes between the idps and the boko haram insurgents who equally look out for similar items for its commercial value to sell and feed their numerous harem of women and children with them in the bush. However, with the early clamp down on non governmental organizations (NGO’s) who were sympathetic to the cause of the insurgents in the name of balancing acts, it became harder for the terrorists to maintain their harems and their kids. They had to desperately look for alternative plans to survive especially with the factionalization of the jihadists. Indeed former theatre Commander, General Adeniyi once shut down about three NGO’s fingered in such sympathetic practices but they were later allowed to resume operations by some powers that were from Abuja. But what ever was trickling to the insurgents was completely cut off according to sources including the controversial mama Boko Haram who had unfettered access to their commanders through her foundation. So having been left high and dry in the bush, they too started sending their wards out to scavenge not only for ajaokuta but for abandoned plastic containers and firewood. This was meant to assist their bush economy which Adeniyi did not want to thrive even as they farmed and fished in the lake Chad axis unhindered.

Consequently, it was the scavenging for these items that used to bring lingering fracas between the IDPs and the insurgents.

The most bloody skirmish in recent times

Not too recently in Rann, the headquarters of Kala Balge the idps were said to have strayed several kilometers beyond where they were supposed to stay in search of these scraps which would amount to immediate cash once they meet the right dealers. Over 40 residents on a scrap metal scavenging spree were slaughtered by insurgents believed to be of the Islamic State of West Africa (ISWAP) stock. The killings which took place when ISWAP insurgents carrying rifles and knives rounded up a group of idps that were searching for scrap metals to sell for a living. About 47 of the scavenging camp residents who were looking for the “Ajaokuta ” were rounded up and slaughtered for daring into the known territories of the insurgents. That singular act of butchery sources told this reporter became very painful to the Governor Babagana Zulum who vowed to ban the activities of the residents and idps over ajaokuta. But are they really banned considering the fact that there are no specific check points monitoring it’s movements?

Transition to plastics and fire wood

After the banning, the idps usually confined within 5km of their council headquarters now settled for the used battered plastics trade which had existed long before the boko haram challenge started. The ajaokuta business goes on secretly in trickles because they hide them inside used plastic containers and bottles which the security points hardly bother about. Driving through the city of Maiduguri, heaps of plastics can now be seen around certain areas in outskirts like Gubio road, Baga road and several suburbs where cart pushers ask for so called condemned items to go sell. And these are weighed on scales and instant cash is awarded for those who are bold enough to penetrate Garbage bins and dump sites to get the plastics which are gathered like Ajaokuta.

Fire wood is equally not left out of the foraging business. As a matter of fact, firewood has become the second largest revenue earner for resident IDPs in the state capital. The camps may have closed officially but a lot of resident IDPs who live with relatives in the metropolis go hunt for firewood in the thick savannah and sell to residents most of whom have abandoned charcoal which moved from N3,000 to N10,000 a bag. This has forced many civil servants in the upper lower class to move down to fire wood as the new savior. So with firewood dumps in almost every crevice of the state now, it has become a safe alternative to these ajaokuta scraps some of which have become death traps because residents usually walk into improvised Explosive Devices (IEDS) planted by insurgents in the name of hunting for them. Many innocent souls have perished in that process.

However. If residents in key towns in the state must fulfill their destinies to generate enough revenue to feed themselves, since free feeding may be terminated this year, then fire wood scavenging has come to stay as a veritable index in fulfillment of their individual desires. Firewood and plastics have become a heavy source of bush market revenue which even the government can utilize in beefing up it’s internal revenue. The mantra of plant trees where others are felled can only apply where there is safety. Nobody can tell residents of tashan Kano and surrounding suburbs down to Bulumkutu who go into the nearby Molai bush to source for fire wood to plant one tree there. His or her business is to grab the wood and return back quickly before the armed men in the other side come out to look for theirs. That is the new slogan of the down trodden in Borno state.

Features: Two years after the ajaokuta ban in Borno, insurgents and residents now scavenge for plastics and firewood

Feature

Public Institution Should be Run with Integrity, Efficiency and Vision- Justice Umar

Public Institution Should be Run with Integrity, Efficiency and Vision- Justice Umar

By: Michael Mike

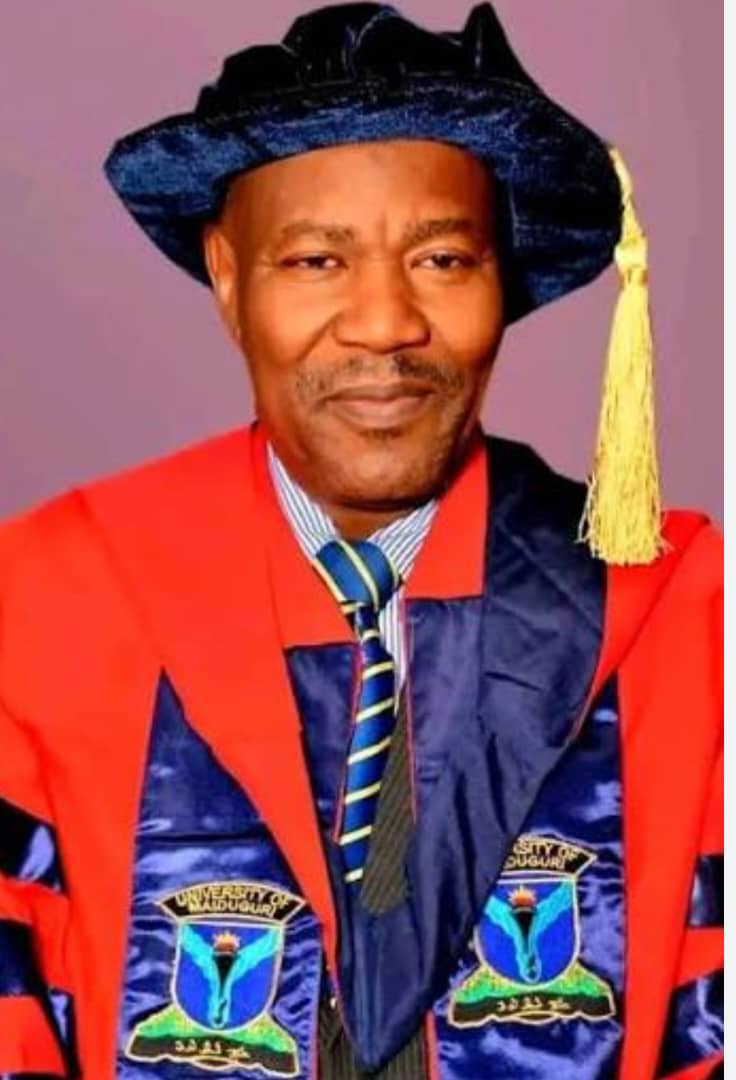

Honourable Justice Mainasara Ibrahim Kogo Umar, Chairman of the Code of Conduct Tribunal of Nigeria, embodies discipline, depth, and judicial conviction. A man of impeccable character and tested integrity, he is widely regarded as dependable in moments that demand courage and clarity. With decades of experience in legal practice, public service, and institutional leadership, he stands as one who has truly “been there and done that.”

His record reflects landmark contributions—both individually and collectively—shaping conversations around accountability, constitutional responsibility, and anti-corruption enforcement. Justice Kogo Umar represents a compelling study in legal pragmatism, institutional reform, and principled leadership.

In this interview with a select group of journalists, he speaks candidly about reforming the Tribunal, strengthening anti-corruption mechanisms, and his broader vision for justice and public governance in Nigeria, excerpts:

Question: Good afternoon sir, can we meet you?

My name is Mainasara Ibrahim Kogo Umar. I hail from Katsina State. I come from an aristocratic background, but over the course of my journey in unionism and activism, I became deeply influenced by Marxist ideals.

I have been involved in many spheres of life, particularly activism and legal practice. I have fought against corruption for several decades. Currently, I serve as the Continental President of the African Transparency Front, among other responsibilities.

I was appointed Chairman of the Code of Conduct Tribunal on 13th July 2024, after 23 years of leaving the organisation. I previously served here as a young lawyer and later as Chief Registrar of the Tribunal before pursuing other endeavours.

By God’s infinite mercy, I have returned as Chairman of the Code of Conduct Tribunal. My appointment generated some controversies because the President deemed it necessary to revitalise this very important institution.

The Code of Conduct Tribunal is the only judicial institution specifically mentioned in the Constitution under the Fifth Schedule. It tries public officers on matters relating to breaches of the Code of Conduct, abuse of office, illicit enrichment, ostentatious living beyond legitimate earnings, and issues of ethics and morality.

As Chairman, one must be above board. You are the arbiter who determines the personal and official conduct of public officers.

The Constitution clearly defines who public officers are. They include the President of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, the Vice President, ministers, members of the National Assembly, members of the diplomatic corps, service chiefs, judges—including Justices of the Supreme Court and the Chief Justice of Nigeria—members of academia in public institutions, and anyone at the federal, state, or local government level who earns a salary from public funds.

The Tribunal’s mandate is not restricted to asset declaration alone. Even if you declare your assets beyond three months after assuming office, you are already in breach. Subsequently, every four years—whether appointed, elected, or employed—it is mandatory to declare your assets. This serves as a benchmark to determine whether your acquisitions align with your legitimate earnings.

Public officers are not permitted to engage in private business or trade while in office, except farming. If you wish to enter politics, you must resign before contesting.

Upon appointment, the Chairman of the Tribunal can only be removed under three circumstances:

1. Upon attaining the age of 70;

2. By voluntary resignation;

3. For misconduct or breach of the Code of Conduct, in which case both chambers of the National Assembly must invoke their constitutional powers to remove the Chairman.

The Senate, on 20th November 2024, exercised this power and removed the former Chairman on grounds of abuse of office and misconduct. On 26th November 2024, the House of Representatives affirmed the removal with an overwhelming majority.

On 20th February 2025, the Secretary to the Government of the Federation presented my appointment letter, backdated to 20th November 2024. I was subsequently inaugurated by the President and sworn in on 7th October 2025.

What was the state of the Tribunal when you assumed office, and what are the current challenges and your vision?

When I assumed office, the Tribunal was in a very poor state. Staff morale was low, infrastructure was dilapidated, there was no electricity or water supply, and furniture was grossly inadequate.

I immediately restored electricity and water supply, reactivated boreholes, revitalised transformers, and sought technical assistance. Through outreach to international agencies, we secured computers, laptops, photocopiers, and other equipment.

I restructured the institution by expanding it from three departments to thirteen, aligning it with my vision.

One major vision is to transform the Tribunal into the Code of Conduct and Anti-Corruption Court, in line with Section 15(5) of the Constitution, which mandates the State to abolish corrupt practices and abuse of office. A bill to that effect has passed second reading at the National Assembly. If passed, anti-corruption agencies would prosecute relevant cases here.

How does the Tribunal collaborate with agencies like EFCC and ICPC?

Currently, the ICPC prosecutes at State High Courts, while the EFCC prosecutes at the Federal High Court. However, under the proposed reform, cases involving public officers could be prosecuted here.

This Tribunal operates summary jurisdiction. Before assigning hearing dates, I require lawyers to file all written submissions in advance. After reviewing them, hearings focus on adoption and cross-examination, and judgments are delivered promptly. Ideally, no case should last more than six weeks.

The Constitution prescribes specific penalties, including removal from office, disqualification from public office for up to ten years, and forfeiture of ill-gotten assets. These are without prejudice to other criminal penalties under the law.

We have also created departments for international liaison—including collaboration with Interpol and international courts—and enforcement of judgments.

How do you ensure fairness in high-profile cases?

The Tribunal does not initiate cases. The Code of Conduct Bureau investigates and refers cases, while the Attorney General prosecutes. We handle adjudication.

We do not consider status or public pressure—only facts, evidence, and the law. Decisions are reached collectively by a panel of three judges. Public expectation, institutional responsibility, and the demands of the law must be carefully balanced.

How many cases have been referred since your assumption of office?

I inherited thousands of cases, some dating back over two decades. After discussions with the Bureau, we agreed that only cases within a reasonable timeframe—preferably within three years of occurrence—should be referred to ensure effectiveness.

Currently, we handle between two and five cases weekly. The Bureau determines which cases to refer.

What is your vision for the Tribunal in the next five years?

In the next five years, the Tribunal should be placed on first-line charge to guarantee financial independence. We should expand to at least 36 judges, with judicial divisions across the six geopolitical zones and Abuja.

Funding must increase significantly to support infrastructure, security, and institutional growth.

I have served in public service for 36 years and have never taken illegal money. A significant portion of my earnings has gone to charity. My goal is to reposition this institution as a model of public governance and exemplary leadership.

Within five years, once the institution is fully reformed and functioning optimally, I intend to step aside. I do not wish to remain in office until retirement age. My mission is to rebuild, reposition, and leave behind a strong, sustainable institution.

I aim to demonstrate that public institutions can be run with integrity, efficiency, and vision.

Public Institution Should be Run with Integrity, Efficiency and Vision- Justice Umar

Feature

Celebrating the Legendary Malam Umaru A. Pate

Celebrating the Legendary Malam Umaru A. Pate

By Hamza Idris

Tuesday, February 10, 2026, marks his last day as the Vice Chancellor of the Federal University Kashere, Gombe State.

The world saw him smiling as he bade farewell to the university community, as captured in stories and tributes by those who know him, and carried by multiple print and broadcast media platforms.

In journalism, his tenure at Kashere is what is aptly described as a success story, and his departure can fittingly be termed a glorious exit.

Many of us call him Malam as a mark of reverence because we find it very difficult to look into his eyes and call him Prof. The reason is simple: by the Grace of Allah, he made many of us what we are today.

Malam Pate was not alone in shaping our journey while we were at the Department of Mass Communication, University of Maiduguri (UNIMAID). We also had Malam Danjuma Gambo, Malam Abubakar Muazu, Malam Alhaji Musa Liman (late), Malam Mohammed Gujbawu (late), Malam Mustapha Mai Iyali, Malam Nasiru Abba Aji, Mr Udomiso, Mr Nwazuzu, Malam Musa Konduga, Malam Hassan A. Hassan, Madam Ramla (late), Malam Musa Giwa (late), and Malam Alabura (late). I hope I have got all the names correctly, among others. They all impacted our lives positively, and we remain eternally grateful.

But today is Malam Pate’s day, and HERE IS MY STORY ABOUT HIM, which I have told again and again at different fora, and which I am glad to tell once more today.

The best way to tell his story is by using the parable of the blind men and the elephant. Here it is:

Once upon a time, a group of blind men heard that a strange animal called an elephant had been brought to their village. None of them had ever encountered one before, so they decided to learn what it was like by touching it.

Each blind man approached the elephant from a different side.

The first man touched the elephant’s leg and said, “An elephant is like a pillar—strong and firm.”

The second man touched the tail and said, “No, the elephant is like a rope, thin and flexible.”

The third man touched the trunk and declared, “You are both wrong. An elephant is like a thick snake.”

The fourth man touched the ear and insisted, “An elephant is like a fan, wide and flat.”

The fifth man touched the tusk and said confidently, “The elephant is like a spear, hard and sharp.”

Soon, the blind men began to argue. Each believed he alone was right and that the others were wrong, even though each had touched only one part of the elephant.

A wise man who was passing by listened to their argument and said, “All of you are right, and all of you are wrong. Each of you has touched only a part of the elephant. Because you cannot see the whole thing, you think your part is the entire truth.”

The blind men fell silent, realizing that the truth was greater than any single perspective.

This parable clearly tells us the man Malam Pate. You only tell what you know about him but to him, all his proteges are his favourites.

After we graduated from UNIMAID in 2002 and completed our NYSC, I continued with the job that was available at the time—teaching.

In 2005, Daily Trust newspaper had a vacancy in Yola, Adamawa State, and the then Bureau Chief, Malam Abdullahi Bego (also an alumnus of Mass Communication, UNIMAID and currently the Commissioner of Information in Yobe State), was tasked with the responsibility of getting the right person and he reached out to Malam Pate to nominate anyone he felt could serve as State Correspondent in Adamawa.

Malam Pate then contacted one of our classmates, Amina Mohammed. However, for some obvious reasons, Amina did not take up the job. Instead, she informed Malam Pate that I was yet to secure a proper job in line with what I studied at the university.

He asked her to tell me to call him, which I did. Amina currently works at the information unit of Federal Medical Centre, Yola. I remain eternally grateful to her.

Malam Pate then linked me up with Malam Bego after vouching for my integrity and passion for the job—and that was it. I was offered automatic employment as a Reporter and Researcher—no interview, nothing.

This was over 20 years ago. Only God knows the number of people who secured jobs through Malam Pate. The mere mention of his name clears the pathway. It is very unlikely to visit five establishments in Abuja and any other state, provided they have a public affairs directorate, without seeing someone that got there through Malam.

It is very unlikely to visit any media organisation in Nigeria (newspaper, radio or television) without coming in touch with someone that benefited from Malam through training or mentoring. It is also very unlikely to visit any faculty or department of mass communication or journalism in any university or polytechnic in Nigeria, without seeing someone who studied under Malam, or benefitted from his supervision or mentorship in the course of his studies. He is a real benefactor.

Malam Pate is one of the guarantors on my CV. The other two are my former Editor-in-Chief, Malam Mannir Dan-Ali, and Malam Bego. Over the past 20 years, I have secured dozens of fellowships and trainings, both at home and abroad, largely because their names appear on my résumé. I also presented endless papers at high profile gatherings, all because some good people told others that yes, you can do it.

Ahead of the World Press Freedom Day in 2016 or thereabouts, Malam Pate called and asked me to write about my experience covering the Boko Haram crisis under the theme: Professionalism and Risk Management in the Reporting of Terror Groups and Violent Extremism in North-East Nigeria, How Journalists Survived to Report.

He, on his part, wrote the contextual aspect of the topic, shared the byline with me—even though he did the bulk of the work—and went on to present the paper in Helsinki, Finland.

Gladly, the same paper has found its way into at least two books, including Assault on Journalism, edited by Ulla Carlsson and Reeta Poythari, Nordicom, University of Gothenburg, Sweden (2017); and Multiculturalism, Diversity and Reporting Conflict in Nigeria, Evans Brothers (Nigeria Publishers) Limited, which he edited together with Professor Lai Oso (2017).

The paper has also been cited in many MSc and doctoral theses, both in Nigeria and around the world.

Indeed, Malam Pate is a father figure to many of us. Kindly share your experience in the comment section so that we can collectively celebrate this enigmatic figure.

Malam, as you open another chapter in your life after recording this milestone at the Federal University Kashere, may Allah continue to be your driving force, granting you good health and amity as you tirelessly change the face of journalism teaching and practice.

Celebrating the Legendary Malam Umaru A. Pate

Feature

Economic reforms: How did President Tinubu uniquely reshape Nigeria’s economy?

Economic reforms: How did President Tinubu uniquely reshape Nigeria’s economy?

By: Dr Abolade Agbola

In a few months, the economic reforms of the government of President Tinubu will be three years old, while the government will be on the last lap of its four-year first-term mandate.

The President’s statement at his inauguration on the 29th May 2023, that “the fuel subsidy was gone,” ushered in a series of reforms that reshaped the economy. Two weeks after the President’s inauguration, the Central Bank unified the multiple exchange rates on 14th June 2023 and transitioned from a rigid, multi-layered exchange rate system to a unified, “willing buyer-willing seller” managed float regime.

The Presidential Committee on Fiscal Policy and Tax Reforms was constituted in July 2023 to draft a new tax and fiscal law. In March 2024, the Central Bank announced a new threshold for bank capital, requiring banks to increase their minimum share capital by the March 31, 2026, deadline to strengthen the financial system against impending economic shocks following the reforms and support the nation’s economic growth target of $ 1 trillion in GDP by 2030. Nigeria has had several foreign exchange market reforms, but the most profound ones are the transition from the Import licensing scheme to the Second-Tier Foreign Exchange market in 1986, following the deregulation and liberalization of the economy, and the massive devaluation of the currency in 1994. The uniqueness of the 2023 reforms lay in their timing, at the dawn of the administration, and in complementary policies such as the floating of the Naira following the abolition of multiple exchange rates, thus allowing the market to achieve equilibrium simultaneously in the pricing of petrol and the Naira.

The fuel subsidy removal led to a price increase for petrol from N200 per litre in May 2023 to between N1,200 and N1,300 per litre in early 2025. The floating of the Naira and unification of multiple exchange rates led to the currency’s massive devaluation from N460: $1 on 29th May 2023 to N1,700: $1 by November 2024. The post-subsidy removal and Naira floatation in the economy led to high inflation and a decline in household consumption. According to the World Bank, 56% of Nigerians (over 113 million people) living below the poverty line in 2023 are projected to reach 61% (139 million) by 2025.

Today, the Naira is stabilizing at about N1,400: $1, while petrol has fallen to about N880 per litre, and inflation has receded to 15.15%, with prospects of getting to a single digit before the end of 2026. A single-digit inflation rate will take a substantial number of people out of poverty as the mystery index declines alongside the receding inflationary spiral, as policies that foster job creation, reduce price volatility, and stimulate economic growth are implemented.

Nigeria was on the brink of economic collapse in 2023. Most of the sub-nationals were unable to pay salaries. There was no budget for fuel subsidy from 1st June 2023. The external reserves of US$34.39 billion in May 2023 were barely adequate to finance 6.5 months of imports of goods and services and 8.8 months of imports of goods only. JP Morgan, a global financial institution, later claimed that the previous administration actually left Nigeria with a net reserve of $3.7 billion, rather than $34.39 billion. In May 2023, the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) had a foreign currency liability to foreign airlines of approximately $2.27 billion due to the airlines’ inability to repatriate their ticket sales revenue. Nigeria’s foreign reserves stood at $45.21 billion as of December 2025. In fact, the country experienced significant trade surpluses, with reports indicating around N6.69 trillion (Exports: N22.81tn, Imports: N16.12tn) as at the third quarter of 2025, driven by rising crude oil and non-oil exports, such as refined petroleum, despite some fluctuations and policy impacts, highlighting economic restructuring towards diversification.

Nigeria’s economic decline, which compelled the latest reforms, began in 2014, when crude prices began plummeting from their peak of $114 per barrel. Nigeria had two recessions in 4-year intervals, the 2016 recession, when the price of crude oil fell to $27 per barrel due to a U.S. shale oil-inspired glut. The other recession in 2020 was a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, when crude oil prices dropped to $17 per barrel amid worldwide lockdowns aimed at containing it. The economy was rebounding in 2022 when the Russia-Ukraine war disrupted the global commodity supply chain and triggered another round of economic crises.

The government was reluctant to depreciate the Naira in response to economic realities, given its populist and leftist inclinations. The consequence was the near collapse of the economy by the time the 2023 elections were held. The government borrowed massively with the intent of spending its way out of the recession. Nigeria’s total public debt was N77 Trillion, or $108 billion, when President Tinubu was sworn in on the 29th May 2023.

The debt profile had risen to N160 trillion ($111 billion) by the end of 2025, a moderate growth given the significant depreciation of the currency and the vast improvement in the country’s fortunes in the past two years.

Nigeria had intermittently grappled with rent, creating multiple exchange rates since 1986, when the corrupt-laden import license scheme gave way to currency auctions using the Dutch auction method. In 1986, amid the crude oil price meltdown, Nigerians rejected the IMF loan after a debate instigated by the military to carry the people along with the options available at the time for addressing the nation’s economic crisis. The objective of the IMF/World Bank-backed policy was to diversify the oil-dependent economy, reduce imports, privatize state firms, devalue the Naira, and foster private-sector growth to combat worsening economic conditions, such as inflation and debt overhang. In 2023, at its zenith, the rent reached N300 for every dollar sold by the central bank, creating artificial advantages in the market and enabling a few to extract wealth without effort.

No wonder President Tinubu remarked while campaigning that if the multiple exchanges remain for one day after he is sworn in as President, it means he is benefiting from the fraud, and added, “God forbid.”

Fuel price regulation started with the Price Control Act of 1977. The fuel subsidy was introduced around 1986, when we designated fuel stations into two categories. The station that sells to commercial vehicles offers subsidized prices, while the one that sells to private vehicles charges market rates. The arrangement collapsed, and the subsidy regime crept in.

Just as in 2023, Nigeria undertook a massive devaluation of the Naira and the removal of petroleum subsidies in 1994 during the era of General Sanni Abacha. The Naira was devalued from N22 to N80 per dollar in 1994, following the near-collapse of the economy after the annulment of the 12th June 1993 elections and a protracted period of low crude oil prices, which reached $16 per barrel in 1994. Almost simultaneously, the government removed some fuel subsidies and established the Petroleum Trust Fund, headed by the late President Muhammadu Buhari as Chairman, to manage projects funded by part of the removed subsidies.

According to CBN data, inflation rose from 57.03% in 1994 to 72.83% in 1995 due to the policy. The inflationary rate declined to 29.26% in 1996, and 8.52% in 1997, and 9.99% in 1998.

The reforms by President Tinubu in 2023, following the floatation of the Naira and the removal of the fuel subsidy, created a similar inflationary spiral. Inflation rate rose from 22.41% in May 2023 to 28.92% in December 2023, marking a 21-year high. The surge in inflation peaked at 34.80% by December 2024. The year-on-year inflation, however, declined to 15.15% by December 2025, indicating improving price stability as we approach the third year of the reforms.

There is no doubt that inflation will recede to single digits before the end of 2026 as the trigger factors (petrol prices and exchange rates) are now determined by market forces.

The reforms of President Tinubu in 2023 were unique in several ways. The courage to embark on both fuel subsidy removal and floatation of the Naira simultaneously at the dawn of the regime amounted to front-loading the expected and inevitable policy pains for gains that will manifest as the administration winds down its first term in office. What is certain after discounting for possible, unpredictable global headwinds such as commodity price volatility, the pandemic, climate change, and supply chain disruptions, to name a few, is that the economy will continue to improve as we approach the election year.

The trend will certainly play a key role in the 2027 elections. Unlike the 1994 subsidy removal and devaluation of the Naira, during which a portion of the fuel subsidy removal benefits was allocated to the Petroleum Trust Fund(PTF), the benefits of the 2023 policy actions were equitably and transparently shared among the three tiers of government, thereby strengthening the fiscal position of the federating units.

The inequitable distribution of PTF projects among the federating units remains a recurring point of criticism of the initiative. Monthly allocations to the 36 states and 774 local councils increased from roughly ₦458.81 billion in May 2023 to over ₦991 billion by June 2025, representing a 116% increase in some periods.

The improved FACC allocation to the states may be one of the reasons for the cordial relationship between most of the state governors and the federal government, as the states were able to execute many projects to fulfill their campaign promises.

Another unique foresight of the government in implementing the 2023 reforms is the recapitalization of banks to strengthen financial institutions, as the Naira weakens amid a spike in inflation. The massive devaluation of the Naira in 1994 led to a wave of bank failures some years later.

According to Central Bank reports, by 1998, 20 distressed banks had had their licenses revoked, with dire consequences for the economy. The 2024 banking recapitalization, ending March 2026, which gave banks a 24-month window to shore up their capital, was a masterstroke to strengthen the financial system, build stronger, more resilient banks to withstand Naira depreciation shocks, and foster sustainable economic growth and development.

The brand-new set of tax and fiscal laws delivered by the Presidential Committee on Fiscal Policy and Tax Reforms became operational on the 1st of January 2026.

The law aims to remove all barriers to business growth in Nigeria and further diversify the economy by enhancing its revenue profile, weaning the nation from reliance on crude oil export revenue.

The laws are to enhance revenue collection efficiency, ensure transparent reporting, and promote the effective utilization of tax and other revenues to boost citizens’ tax morale, foster a healthy tax culture, and drive voluntary compliance.

The government, after protracted negotiations with labour unions, reviewed the national minimum wage in July 2024, from ₦30,000 to ₦70,000 per month, to mitigate the impact of inflation, one of the most debilitating unintended consequences of the reforms. The government, in a proactive move, promulgated the National Minimum Wage Amendment Act 2024 to shorten the minimum wage review period from 5 years to 3 years, meaning that the next formal review is due in 2027.

There are several other projects and programmes aimed at repositioning the economy, such as the massive divestment of onshore oil assets in 2024 by International Oil Companies (IOCs) to indigenous Nigerian firms, which has increased crude oil production from 1.1mbarrel per day in 2023 to around 1.44million barrels per day (mbpd) in 2025. The speedy conclusion of the transfer deals and the rework of the assets is crucial to the actualization of the government’s target of daily production of 2.5m barrels per day in 2026 and the turnaround of the economy for another era of sustainable growth and development.

There is also the deployment of 2,000 high-quality tractors with trailers, ploughs, harrows, sprayers, and planters in 2025 as part of the government’s commitment to inject 2000 tractors annually to improve farming efficiency and reverse the poor mechanization of our farms. Nigeria, with a land area of 92m hectares, of which 34m hectares is arable, has less than 50,000 tractors, which is dismally low and significantly responsible for our food insecurity.

In conclusion, there is no doubt that the President and his team have done many things differently, such as the audacious simultaneous removal of the fuel subsidy and the unification of the multiple exchange rates, the floatation of the Naira, new fiscal and tax laws, the recapitalization of banks, and the minimum wage review.

These are comprehensive monetary, fiscal, and structural reforms that are delivering changes, transitioning our country from a restricted, inefficient, or crisis-prone economy to a more open, market-oriented, and competitive one. The pains uploaded upfront at the inception of the regime are giving way to discernible gains and unprecedented reset of the economy for sustainable growth and development. Our nation is poised to enter another era of pervasive economic boom, having emerged from the bust cycle that began in 2014 stronger.

A solid framework for replicating the economic boom of 2005 to 2014 has been laid by adopting market-determined exchange rates and fuel prices, and by ramping up crude oil production. The government must evolve pragmatic trade and investment policies to mitigate some of the unintended consequences of the reforms, such as dwindling household consumption, escalating inequalities, and the percentage of people living below the poverty line, while protecting local industries, attracting foreign investment, boosting job creation, and enhancing the standard of living of the people. Nigeria is no doubt set for another era of sustainable growth and development.

Dr Abolade Agbola, DBA, MSc Ag Econs, FCS, FCIB, Managing Director of Lam Agro Consult Limited and Lam Business Solutions, is a Stockbroker, Banker, and Agribusiness Business Consultant .He writes from Lagos

Economic reforms: How did President Tinubu uniquely reshape Nigeria’s economy?

-

News2 years ago

News2 years agoRoger Federer’s Shock as DNA Results Reveal Myla and Charlene Are Not His Biological Children

-

Opinions4 years ago

Opinions4 years agoTHE PLIGHT OF FARIDA

-

News10 months ago

News10 months agoFAILED COUP IN BURKINA FASO: HOW TRAORÉ NARROWLY ESCAPED ASSASSINATION PLOT AMID FOREIGN INTERFERENCE CLAIMS

-

News2 years ago

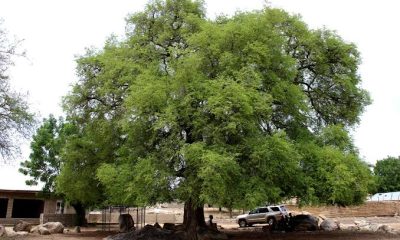

News2 years agoEYN: Rev. Billi, Distortion of History, and The Living Tamarind Tree

-

Opinions4 years ago

Opinions4 years agoPOLICE CHARGE ROOMS, A MINTING PRESS

-

ACADEMICS2 years ago

ACADEMICS2 years agoA History of Biu” (2015) and The Lingering Bura-Pabir Question (1)

-

Columns2 years ago

Columns2 years agoArmy University Biu: There is certain interest, but certainly not from Borno.

-

Opinions2 years ago

Opinions2 years agoTinubu,Shettima: The epidemic of economic, insecurity in Nigeria