News

Rebuilding Zamfara in a Complex Era – The Dauda Lawal Style

Rebuilding Zamfara in a Complex Era – The Dauda Lawal Style

By: Zagazola Makama

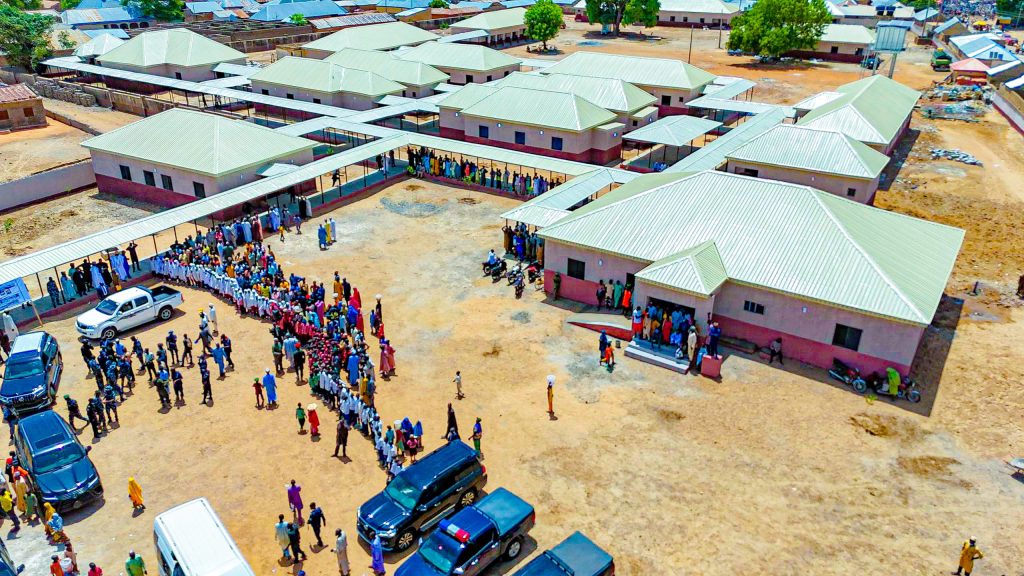

In the intricate landscape of Zamfara State’s recent history, a transformative chapter unfolds with the governance of Dauda Lawal. Amidst the shadows of banditry, poverty, and institutional decay, his tenure as the 5th Executive Governor emerges as a beacon of hope and resilience. Through a tapestry of strategic reforms and resolute actions, Governor Lawal orchestrates a bold revival of Zamfara’s fortunes, championing security, education, healthcare, infrastructure, and empowerment initiatives. As the state grapples with the legacy of past challenges, Zagazola Media Network Team who was in Zamfara recently, has in this captivating piece, captures how Governor Lawal’s leadership shines as a testament to visionary governance in a complex era, heralding a new dawn of progress and prosperity for Zamfara.

In the last decade, Zamfara State, like its neighbor in the North-West region, has been engulfed by banditry, kidnapping, and other crimes that threatened the social fabric and economy of the state. Many people were killed, and thousands displaced, while large-scale destruction of public and private properties was perpetrated by the bandits, resulting in a serious humanitarian crisis in the state.

Upon his inauguration as the 5th Executive Governor of Zamfara on May 29, 2023, Dauda Lawal inherited Zamfara in a state of bankruptcy characterized by decayed institutions, widespread poverty, and hunger among the citizens, thus eroding the confidence of the people in the government’s ability to navigate the security and economic challenges bedeviling the state.

The past administration had failed to pay workers for four months, leaving them in bad shape. As a passionate leader, Governor Dauda Lawal quickly sourced funds with which he paid off the backlog of four months’ salaries. These included the withheld salaries of local government workers and primary school teachers. To break the shackles of poverty and address the myriad of problems bedeviling the state, the Dauda Lawal administration initiated viable empowerment, social, and economic infrastructure development programs to build a secure, peaceful, and prosperous state.

The November 2022 release of the multidimensional poverty index revealed a troubling statistic for Zamfara: 78% of its population is living in poverty, showcasing a worsening trend under the past government of Matawalle, now a minister in the federal cabinet, as poverty increased from 74% to 78%.

Furthermore, the preceding administration in Zamfara showed inadequacies in debt management. In 2019, according to a report by Premium Times, Zamfara’s total debt, including both domestic and external, stood at N103.35 billion. This figure climbed to N130.1 billion in 2020 and further increased to N130.94 billion in 2021. Shortly before Governor Lawal took over power, the state held the second-highest debt burden in the North-West region and ranked 15th among the 36 states of the federation in terms of debt levels.

Despite inheriting an empty treasury, Governor Dauda Lawal has so far kept to his campaign promises and has accomplished major strides in key sectors to rescue and rebuild Zamfara under his Six Smarts Agenda

Securing Zamfara

To end banditry and other security breaches in the state, the Lawal administration demonstrated high commitment to curb the lingering banditry and kidnapping. This singular commitment led to the establishment of the Zamfara Community Protection Guards (CPG), also known as “ASKARAWA,” the pioneer security guard corps in the North-West region. Members of the guard corps underwent rigorous physical and regimental training to prepare them to assist the security agencies with credible intelligence to combat insecurity. The group has been very helpful in foiling bandit attacks in villages and towns across local government areas of the state. This has given the people hope for safety and security.

Other security-related interventions by the governor included the provision of logistics and equipment to the security agencies, such as fueling of patrol armored vehicles, and repairing patrol vehicles to improve the security presence throughout the state, as well as conducting periodic meetings of the State Security Committee. Also, the Lawal administration, through collaborative operations with the security agencies comprising the Nigerian Army, Police, State Security Services, NSCDC, among others, successfully neutralized key bandit kingpins including Kachalla Ali Kawaje, the mastermind of the abduction of students of the Federal University Gusau. Other neutralized bandits are Kachalla Jafaru, Kachalla Barume, Kachalla Shehu, Tsoho, Kachalla Yellow Mai Buhu, Yellow Sirajo, Kachalla Dan Muhammadu, Kachalla Makasko, Sanda, Abdulbasiru Ibrahim, Mai Wagumbe, Kachalla Begu, Kwalfa, Ma’aikaci, Yellow Hassan, Umaru Na Bugala, Isyaka Gwarnon Daji, Iliya Babban Kashi, Auta Dan Mai Jan Ido, and Yahaya Dan Shama.

Education Revolution

Recognizing the crucial link between education and development, the Dauda Lawal administration declared a State of Emergency in the education sector. This initiative aimed to combat illiteracy, empower the youth and women, and establish a strong foundation for sustainable social and economic progress in the state.

The governor has implemented sound school infrastructure and teacher development programs in the past year in office. The projects are designed to correct the deteriorating state of education inherited from the previous administration and revive the sector to conform with best international standards. The Lawal administration paid N1.4 billion in outstanding examination fees for indigent students who sat for the West African Examination Council (WAEC) and Senior Secondary Certificate of Education (SSCE in the past three years. WAEC had released all the withheld results following the payment of the examination fees owed by previous governments. Similarly, Governor Lawal approved and ensured the payment of the National Examination Council (NECO) fees for all public school candidates who sat for the 2023 exams. Certificates for the candidates who sat for the 2019 NECO examinations have since been collected and distributed to the students.

The results of the NECO exams taken in 2020, 2021, and 2022 were also released to students in November 2023. The results were previously withheld by the examination body due to defaults in payment by the previous administration. It is heartwarming to note that with Lawal’s intervention, students who graduated during those years can now access their results and apply to different tertiary institutions for admission.

In terms of infrastructure, the Lawal administration has started the construction and renovation of 245 schools spread across the 14 Local Government Areas (LGAs) of the state. This effort involves not only renovating these schools but also providing two-seater desks for 9,542 pupils and students, furnishing 1,545 tables and chairs for teachers, and carrying out the rehabilitation and remodeling of 28 schools throughout the state.

To address the menace of out-of-school children and encourage girl-child enrollment and retention in school, the Lawal administration contributed N150 million as a counterpart fund to fast-track the implementation of the Adolescent Girls Initiative For Learning And Empowerment Additional Financing (AGILE-AF). AGILE-AF is a World Bank education intervention program aimed at empowering young girls to complete basic education and acquire skills to enable them to become self-reliant and contribute to the development of society.

Governor Lawal has also provided office space to the project implementing team and conducted a Needs Assessment exercise in 123 basic and post-basic schools and 40 non-formal Islamic schools in the state. In his determination to provide a safe and conducive learning environment, the Dauda Lawal administration has revived the school feeding scheme in 10 senior boarding schools for the 2023/2024 academic session, while extending scholarships and bursary awards to cover tuition fees of students studying in Nigerian institutions and overseas, including Sudan, Cyprus, and India. This gesture is to ensure the seamless progression of their academic pursuits.

Lawal has also sponsored 50 percent of Zamfara indigenes admitted into the Federal Government Girls College Gusau for the 2023-2024 academic sessions. To buttress its drive for ensuring access to quality education, the governor approved the suspension of the licenses of private education providers in the state. This ensures that private schools meet the required standards for providing quality education in a comfortable environment with well-trained teachers, quality infrastructure, and necessary equipment. Governor Dauda Lawal constructed additional classrooms and renovated the exam halls.

Transforming Healthcare Services

On January 30, 2024, Governor Dauda Lawal declared a state of emergency in the health sector, with a view to tackling the rot in the system and transforming the sector towards the delivery of quality healthcare services in the state. To this end, the Lawal administration rolled out infrastructure and capacity development projects in health facilities across the state. The projects include rehabilitation and provision of equipment at the general hospitals in Maradun, Maru, Kauran Namoda, Gusau, and the primary health center in Nasarawa Burkullu, as well as the rehabilitation of the School of Health Technology, Tsafe.

Importantly, Lawal has organized a Special Modified Medical Outreach Program to address critical healthcare needs and improve people’s quality of life. The outreach provided free medical services to people with cases of cataracts, groin swellings (hernias, hydroceles), Vesico Vaginal Fistula (VVF) repairs, and health education. This is the first time in Zamfara’s history that the state government is engaging in a free medical outreach that covers such critical areas; the ongoing modified outreach utilizes tele-screening for patients from rural and semi-urban areas to provide specialized care to people in need.

About 1,858 persons had so far benefited from the free medical outreach across the 14 LGAs in the state, including 747 groin swellings, 246 swellings & lumps, 781 cataract surgeries, and 84 VVF repairs, as well as the supply of medical supplies to hospitals across the state.

Enhancing Access to Clean Water

For many years, residents of Gusau, the state capital, and other parts of the state have been experiencing acute water shortages due to the collapse of urban and rural water schemes, a situation that forced them to rely on unwholesome water sources. However, the governor conducted a total turnaround maintenance of the facilities to ensure a steady water supply to meet the growing demand of the population. Today, most parts of the state enjoy access to potable water.

Civil Service Reform

Upon taking office, Dauda Lawal initiated a civil service reform program aimed at revitalizing the workforce. This program focused on capacity-building training, creating conducive work environments, and introducing improved welfare packages. These efforts were designed to cultivate a dynamic and results-driven workforce to propel the development agenda of his administration.

Some of the laudable achievements include the payment of withheld salaries of workers. The immediate past administration owed four months’ salaries to the workers. In appreciation of the workers’ contributions to the attainment of government policies and programs, as well as concern for their welfare, Dauda Lawal quickly sourced funds to pay off the backlog of four months’ salaries, including the withheld salaries of local government workers and primary school teachers. The governor approved the payment of N4 billion in backlog gratuities to retired workers owed since 2011. Workers also received a 10 percent leave grant for the first time in the history of the state.

Regarding restructuring, the Lawal administration has reduced the number of ministries in the state from 28 to 16, and the number of Permanent Secretaries from 48 to 23. This is to reinvigorate the service, promote good work ethics and productivity, cut government expenditure, and promote transparency and accountability in the service.

Road Infrastructure/Urban Renewal Project

On August 18, 2023, the Dauda Lawal administration embarked on massive road construction projects under the Urban Renewal Project in Gusau and other major towns in the state. The first phase of the project involves reconstructing and improving 3.5 km of township roads in Gusau and enhancing the drainage system. The project was awarded to Ronchess Nigeria Limited, starting from Bello Barau Roundabout – Old Market Road, Bello Barau Roundabout – Central Police Station Road, Bello Barau Roundabout – Government House Road, and Kwanar Yan Keke – Emir’s Palace – Tankin Ruwa Road.

A 14-kilometer dualized road was also awarded to the construction giant to link Government House – Lalan Mareri, Government House – Sule Zumunci Pharmacy, and Danlarai Mosque – Nasiha Pharmacy, as well as reclaiming the government house gate and landscaping. A 3.4 km dual carriageway project was awarded to TRIACTA Nigeria Ltd, from Lalan Sokoto Road – Government House, and the construction of 13 km township roads was awarded to MOTHER CAT NIG. LTD for the relocation of Lalan – Lalan New 7 numbers of township roads.

Some of the completed road projects, like the Freedom Square – Nasiha Chemist Junction and Freedom Square – Government House – Lalan – Gada Biyu, were commissioned in June 2024 by a former Governor of Bauchi State, Ahmed Mu’azu.

Other projects that have been executed include the renovation and furnishing of the state secretariat complex, rehabilitation of courtrooms, legislative quarters, NYSC Camp, recovery of the Governor’s Lodge Kaduna, and remodeling of Sardauna Memorial Stadium, Gusau.

The Governor also approved the award of the contract for the construction of the Ultra-modern Central Motor Park to Fieldmark Construction Ltd, amounting to N4.8 billion, as part of a crucial component of the state’s Urban Renewal Program that will significantly enhance the state’s transport infrastructure and service delivery.

Empowering Youths and Women

The Dauda Lawal administration has so far empowered 1,500 youths and women to reduce poverty and provide employment opportunities under the Zamfara Youth Sanitation Programme (ZAYOSAP). ZAYOSAP is an integral part of the urban renewal project designed to make Gusau and its environs hygienic, clean, and safe for residents.

Another landmark achievement of the administration is the implementation of environmental protection projects under the ACReSAL program and Ministry of Environment ecosystem. These include contracts for the procurement and installation of solar-powered boreholes in five communities and the construction of five earth dams to provide potable drinking water for people and animals, as well as irrigation.

Governor Dauda Lawal negotiated with the Kaduna Electricity Distribution Company (KAEDCO) to restore electricity supply to all government agencies, which had been without power for many years due to non-payment of N1.2 billion in electricity bills.

To further enhance good governance, Governor Dauda Lawal has recently signed an agreement with several development partners, including UNICEF, the World Bank, and the Melinda & Gates Foundation, and settled the ground rent for the Governor’s Lodges in Abuja and Kaduna.

Makama is a Counter Insurgency Expert and Security Analyst in the Lake Chad region.

Rebuilding Zamfara in a Complex Era – The Dauda Lawal Style

News

Oasis Magazine Apologizes To Hon Ebizi Ndiomu, Retracts Publication

Oasis Magazine Apologizes To Hon Ebizi Ndiomu, Retracts Publication

By John Tega

The management of Oasis Magazine has apologized to Mrs. Ebizi Brown Ndiomu, the lawmaker representing Sagbama Constituency II in the Bayelsa State House of Assembly, following a publication on its online platform, oasismagazine.com.ng on February 20, 2026, with headline: ‘Adulterous Conduct Modeling Around Loikpobiri over Deputy Office.

In a statement signed by the publisher, Daniel Dafe Umukoro, said his attention was drawn to the publication recently, adding that the story sent in by one Diepreye Bagou (07034287403) from Bayelsa does not reflect the standard of the media house.

He added: “We have done a thorough check on the lawmaker and found out that the report crossed the red line.”

He continued: “Mrs. Brown is a respected lawmaker and the allegations made against her are untrue and hereby retracted.”

He said further: “The management apologises profusely to the lawmaker for any embarrassment the publication may have caused her and those close to her.”

Adding: “Oasis Magazine is not known for blackmail or propaganda and this report is hereby trashed and considered done in error.”

Umukoro hinted that going forward; the media house will upgrade mechanisms to avoid such pitfalls.

Oasis Magazine Apologizes To Hon Ebizi Ndiomu, Retracts Publication

News

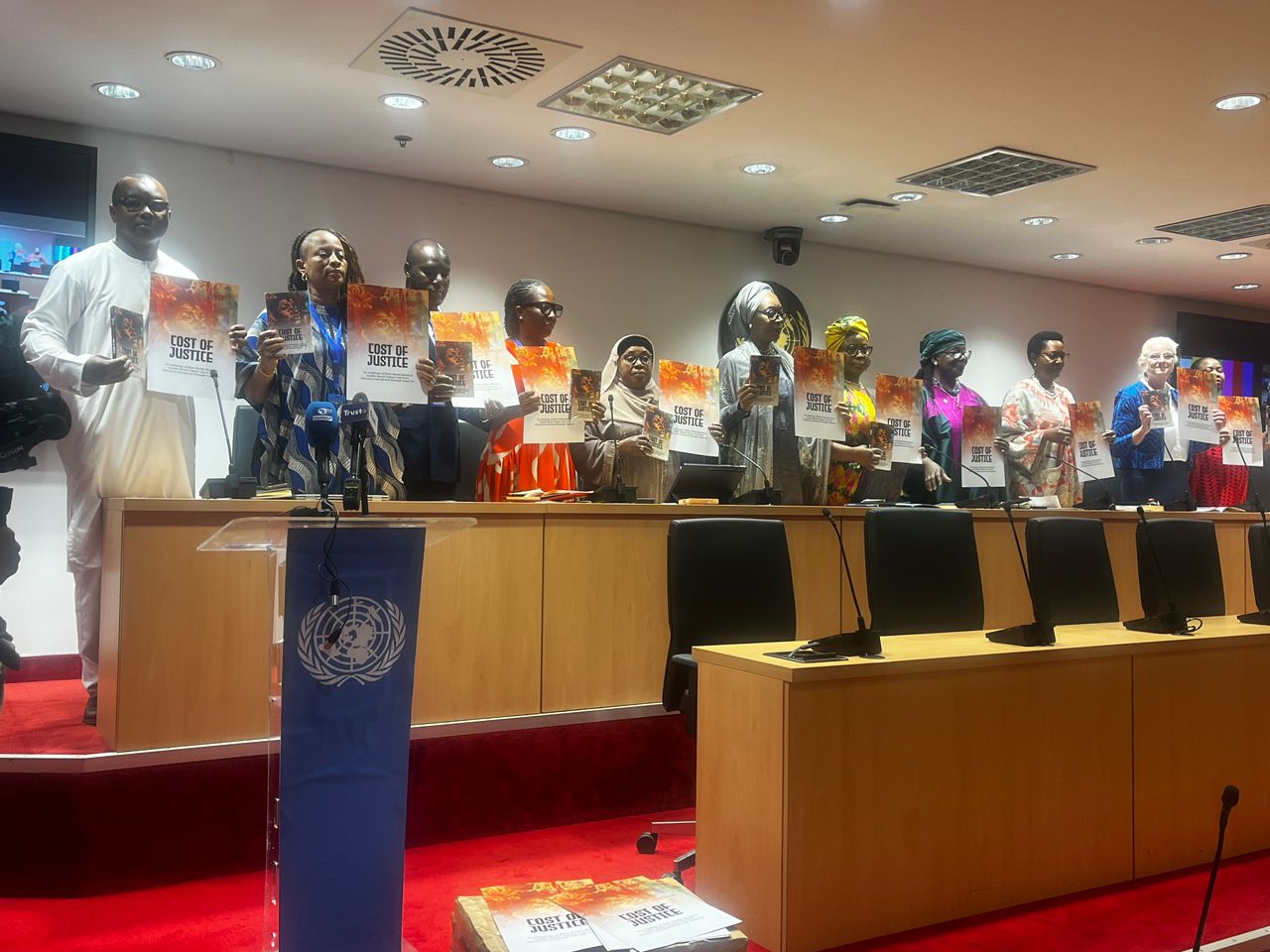

Justice Must Be Affordable, Accessible for Women, Says UN

Justice Must Be Affordable, Accessible for Women, Says UN

By: Michael Mike

The acting UN Resident and Humanitarian Coordinator in Nigeria, Elsie Attafuah, has called for urgent action to reduce the financial, social and institutional barriers preventing women and girls from accessing justice in Nigeria.

Attafuah made the call in Abuja on Friday during the launch of “The Cost of Justice: Women’s Voice of Resilience in Nigeria,” an anthology documenting the experiences of women who have navigated the country’s justice system in pursuit of accountability.

The event, held at the United Nations House in Abuja, was organised by the South Saharan Social Development Organisation in collaboration with UN Women and Ford Foundation as part of activities marking International Women’s Day 2026.

Speaking at the gathering, Attafuah said the anthology serves as a powerful reminder that behind policy debates on justice are real human stories of struggle, resilience and courage.

She noted that many survivors of violence face significant financial burdens when seeking justice, including the cost of transportation, medical reports, legal representation and repeated court appearances.

According to her, these expenses can make the pursuit of justice extremely difficult for many women already facing economic hardship.

She also highlighted the lengthy and complex legal processes survivors must navigate, noting that court proceedings often take months or even years to conclude. During such periods, victims may face pressure from families or communities to withdraw their cases or reconcile with perpetrators.

Attafuah further pointed to the social cost of seeking justice, explaining that survivors frequently encounter stigma, victim-blaming and pressure to remain silent.

She stressed that access to justice is a critical component of global development efforts, particularly under Sustainable Development Goal 16 and Sustainable Development Goal 5, which focus on building inclusive institutions and ending violence against women and girls.

The UN coordinator reaffirmed the commitment of the United Nations system in Nigeria to work with government institutions, civil society groups and development partners to strengthen legal frameworks, expand survivor support services and promote social norms that uphold the dignity and rights of women and girls.

Also speaking at the event, the UN Women Representative to Nigeria and ECOWAS, Beatrice Eyong, said the anthology highlights the persistent challenges women face in accessing justice, particularly survivors of sexual and gender-based violence.

She noted that despite progress in legal reforms and awareness campaigns, many women continue to face financial constraints, stigma and limited access to legal support.

Eyong said the publication documents the experiences and resilience of women who have sought justice, emphasising that justice is not only about laws and institutions but also about protecting dignity and ensuring survivors can seek accountability without fear or hardship.

She commended the organisers and partners supporting the initiative, including the Ford Foundation, for advancing efforts aimed at promoting gender equality and strengthening protection for women and girls.

In a goodwill message delivered on behalf of the Attorney-General of the Federation and Minister of Justice, Lateef Fagbemi, Chief State Counsel at the Sexual and Gender-Based Violence Response Unit of the Federal Ministry of Justice, Habiba Ajanah-Hamza, reiterated the Federal Government’s commitment to improving access to justice for survivors.

She said the ministry remains focused on strengthening coordination among institutions involved in addressing gender-based violence, supporting effective investigation and prosecution of cases, and ensuring that victims are treated with dignity and sensitivity throughout the legal process.

According to her, achieving meaningful access to justice requires sustained collaboration among government institutions, development partners, civil society organisations, the legal community and the media.

Ajanah-Hamza added that initiatives such as the anthology contribute to raising public awareness and strengthening advocacy for reforms that make justice systems more accessible and responsive to the needs of women and girls.

The anthology launch also featured discussions aimed at identifying practical solutions and partnerships that can help reduce the cost of justice and improve survivor-centred responses across Nigeria.

Participants at the event stressed that the voices documented in the publication should serve as a call to action for stakeholders to work collectively toward building a justice system that ensures protection, accountability and dignity for every woman and girl.

Justice Must Be Affordable, Accessible for Women, Says UN

News

Zulum Moves to Fix Rural Health Gap in Borno, Approves 473 Medical Workers and 100% Allowance for Doctors

Zulum Moves to Fix Rural Health Gap in Borno, Approves 473 Medical Workers and 100% Allowance for Doctors

By: Michael Mike

Borno State Governor, Prof. Babagana Zulum has approved the recruitment of 473 medical personnel and introduced a 100 per cent rural posting allowance for doctors in a major push to strengthen healthcare services in underserved communities across Borno State.

The dual intervention is aimed at addressing the shortage of skilled health workers in rural areas and improving access to quality medical care for residents outside the state capital.

The Chief Medical Director of the Borno State Hospital Management Board, Abubakar Kullima, disclosed the development on Thursday in Maiduguri, noting that the governor had approved the immediate employment of doctors, nurses, pharmacists, laboratory scientists and community health extension workers.

Kullima explained that the recruitment also includes specialised health personnel and support staff such as perioperative care nurses and primary eye care workers who will be deployed to newly established and existing health facilities across the state.

According to him, the new workforce will be distributed across general hospitals and primary healthcare centres in the three senatorial zones to strengthen service delivery at both secondary and grassroots levels.

He said the move is part of broader reforms by the Zulum administration to rebuild and expand healthcare services in the state following years of conflict that strained public health infrastructure.

Beyond recruitment, the governor has also directed the immediate implementation of a 100 per cent rural allowance for doctors and a 40 per cent allowance for nurses serving in remote communities.

The incentive, approved through a memo to the hospital management board, is designed to attract qualified medical professionals to rural postings where harsh working conditions and limited facilities often discourage deployment.

With the new policy, doctors who accept rural postings will have their remuneration significantly increased, a step officials say is necessary to address the persistent shortage of medical personnel outside major towns.

Health sector observers say the initiative could significantly boost the availability of healthcare workers in rural communities where residents often travel long distances to access medical services.

The recruitment and incentive scheme form part of a series of healthcare reforms undertaken by Governor Zulum, including the approval of special training funds for resident doctors and the commissioning of specialised health facilities such as eye and dental hospitals.

Officials say the latest measures are expected to improve staffing levels in public hospitals, strengthen service delivery and expand access to essential healthcare across communities in Borno.

Zulum Moves to Fix Rural Health Gap in Borno, Approves 473 Medical Workers and 100% Allowance for Doctors

-

News2 years ago

News2 years agoRoger Federer’s Shock as DNA Results Reveal Myla and Charlene Are Not His Biological Children

-

Opinions4 years ago

Opinions4 years agoTHE PLIGHT OF FARIDA

-

News11 months ago

News11 months agoFAILED COUP IN BURKINA FASO: HOW TRAORÉ NARROWLY ESCAPED ASSASSINATION PLOT AMID FOREIGN INTERFERENCE CLAIMS

-

News2 years ago

News2 years agoEYN: Rev. Billi, Distortion of History, and The Living Tamarind Tree

-

Opinions4 years ago

Opinions4 years agoPOLICE CHARGE ROOMS, A MINTING PRESS

-

ACADEMICS2 years ago

ACADEMICS2 years agoA History of Biu” (2015) and The Lingering Bura-Pabir Question (1)

-

Columns2 years ago

Columns2 years agoArmy University Biu: There is certain interest, but certainly not from Borno.

-

Opinions2 years ago

Opinions2 years agoTinubu,Shettima: The epidemic of economic, insecurity in Nigeria