International

Russia can’t erase sovereign state from map, says Biden

Russia can’t erase sovereign state from map, says Biden

U.S. President said the UN resolution against Russia’s annexations in Ukraine, passed with a historic majority, was a message to Moscow that it can’t erase sovereign state from the map.

“Today, the overwhelming majority of the world nations from every region, large and small, representing a wide array of ideologies and governments voted to defend the United Nations Charter.

“It condemn Russia’s illegal attempt to annex Ukrainian territory by force,” Joe Biden said in a statement.

“The stakes of this conflict are clear to all and the world has sent a clear message in response: Russia cannot erase a sovereign state from the map.

“Russia cannot change borders by force. Russia cannot seize another country’s territory as its own,” Biden said.

“Nearly eight months into this war, the world has just demonstrated that it is more united, and more determined than ever to hold Russia accountable for its violations,” the U.S. leader added.

The UN General Assembly on Wednesday condemned Russia’s recent move to annex the eastern Ukrainian regions of Donetsk, Kherson, Luhansk and Zaporizhzhya, by a vote of 143-5, with 35 countries abstaining.

International

Qatar Rejects Iran’s Explanation for Missile Strikes, Says Attacks Hit Civilian Areas

Qatar Rejects Iran’s Explanation for Missile Strikes, Says Attacks Hit Civilian Areas

By: Michael Mike

Qatar has rejected explanations from Iran over recent missile strikes, insisting that evidence shows the attacks struck civilian areas and key infrastructure inside its territory.

The position was conveyed during a phone conversation between Qatar’s Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs, Mohammed bin Abdulrahman bin Jassim Al Thani, and Iran’s Foreign Minister, Abbas Araghchi, amid rising regional tensions.

According to a statement issued by the Qatar News Agency, the Iranian minister had argued that the missile strikes were directed at American interests and were not intended to target the State of Qatar.

However, Al Thani firmly rejected the claim, stressing that available evidence indicated that the strikes affected civilian and residential areas within Qatar, including locations near Hamad International Airport.

The Qatari prime minister further noted that the attacks also threatened critical infrastructure and industrial facilities, including installations linked to the country’s liquefied natural gas production—an industry vital to the nation’s economy and global energy supply.

Describing the development as a grave escalation, Al Thani said the strikes constitute a clear violation of Qatar’s sovereignty and a breach of international law. He warned that actions capable of endangering civilian populations and strategic facilities cannot be justified under any circumstances.

The Qatari leader reiterated Doha’s commitment to regional stability and diplomacy but emphasized that any threat to the country’s territorial integrity would be treated with utmost seriousness.

The exchange underscores the growing strain in relations between Tehran and several Gulf states as tensions across the Middle East continue to intensify, raising fears of wider regional repercussions if the crisis is not contained.

Qatar Rejects Iran’s Explanation for Missile Strikes, Says Attacks Hit Civilian Areas

International

Interrogating the Russian Model in Africa

Interrogating the Russian Model in Africa

By Oumarou Sanou

In recent years, Russian influence in Africa has expanded at a striking pace and with strategic precision. From Bamako to Bangui, Niamey to Ouagadougou, Moscow has presented itself as a dependable alternative partner; one that claims no colonial guilt, imposes no lectures on governance, and attaches no democratic conditionalities to cooperation. In a region fatigued by insecurity and disillusioned with Western engagement, that message has resonated.

But beyond the rhetoric of “Saint Russia” and the carefully cultivated image of a geopolitical “Saviour of Africa” -a narrative amplified across social media-a more fundamental question demands attention: what exactly is the Russian model offering Africa, and does it truly align with the continent’s long-term aspirations for democratic governance, economic transformation, and social stability?

Africa’s post-independence experience has been shaped by recurring governance challenges: corruption, authoritarian leadership, fragile institutions, and predatory elites. These weaknesses have stunted the growth of an empowered middle class, undermined entrepreneurship, and limited inclusive development. After decades of experimentation, the lesson is clear: sustainable progress rests on accountable leadership, institutional strength, rule of law, and political alternation.

If governance reform remains Africa’s unfinished project, then the value of any external partnership must be measured against whether it strengthens or weakens that trajectory.

The issue is not Russia as a nation. Every sovereign state has the right to pursue its interests abroad. The concern lies with the regime’s political structure, which is implicitly promoted as a model. Contemporary Russia is characterised by prolonged executive dominance, limited political alternation, and significant concentration of economic power among a narrow elite. President Vladimir Putin has led the country for a quarter of a century. Opposition space is restricted. Independent media operates under heavy constraints. Wealth is concentrated, and outside a few urban centres such as Moscow and St. Petersburg, economic dynamism remains limited.

This is not an emotional or ideological critique; it is a structural observation. A governance system marked by entrenched oligarchic influence and constrained civic space is unlikely to export a blueprint that empowers pluralism, fosters institutional independence, or nurtures a broad-based middle class, precisely the ingredients Africa needs.

In the Sahel, Russia’s expanding footprint has coincided not with democratic revival, but with the consolidation of junta-led regimes. Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger, now bound together in the Alliance of Sahel States (AES), have sharply pivoted toward Moscow. Yet these countries rank among those with the highest terrorism-related casualties globally. Despite bold promises, insecurity persists and, in some cases, has worsened. Instability increasingly spills beyond their borders, affecting coastal West African states, including Nigeria.

The central question, therefore, is not whether Russia should engage Africa; it can and should, like any global actor. The real question is whether the nature of that engagement strengthens institutions or merely reinforces regime survival.

Partnerships anchored primarily in security cooperation without parallel institutional reform risk deepening political stagnation. Leaders become insulated from domestic accountability. Civic freedoms shrink. Economic diversification slows. Investors hesitate. Youth populations, already restless, lose faith in systems that offer neither alternation nor upward mobility.

Nigeria offers an instructive contrast. Its democracy is imperfect and often turbulent. Corruption remains a challenge. Electoral processes are contested. Yet Nigeria has witnessed peaceful transfers of power between parties. Civil society is active. The press is vibrant and frequently critical. Courts retain the authority, however unevenly exercised, to check executive excess.

These achievements should not be dismissed. They represent the fragile but essential infrastructure of democratic governance.

It is, therefore, troubling when foreign missions publicly attack Nigerian and African journalists for critical reporting, which is a model Moscow is championing in the AES and seeks to extend to other African countries. A model that seems to suppress critical voices and press freedom. Is that what Africa needs? Media scrutiny is not hostility; it is a cornerstone of democratic accountability.

Reciprocity is the foundation of diplomatic respect. One must ask: would any major power accept a foreign embassy publicly disparaging its journalists on its own soil? The answer is an absolute no, but this is what Russia has done and continues to do across Africa. Nigeria’s democratic gains must not be undermined by external pressure.

Against this backdrop, Africa should resist emotional alignment with any global power, whether East or West. The continent’s future cannot be reduced to proxy rivalries or anti-Western symbolism. Strategic autonomy must be grounded in institutional resilience, not in the romanticisation of external patrons.

If Russia seeks genuine partnership, it must demonstrate respect for sovereignty not only in rhetoric but in substance; by investing in long-term economic value chains rather than narrow extractive concessions; by encouraging transparent governance rather than opaque security arrangements; by engaging societies, not merely regimes.

Africa’s demographic reality makes the stakes even higher. The continent’s youth bulge demands inclusive growth, entrepreneurial opportunity, and institutional trust. Development flourishes where citizens can speak freely, build businesses, and hold leaders accountable. Political systems defined by prolonged executive dominance and limited alternation do not historically generate diversified, innovation-driven economies.

Nigeria stands at a crossroads. It can retreat into political immobility or deepen its democratic experiment. The latter path is imperfect and demanding, but it is the only one capable of building durable institutions. Consider the example of former French President Nicolas Sarkozy, who faced conviction and imprisonment for legal violations. Regardless of one’s assessment of France’s foreign policy, the principle demonstrated was clear: no leader is above the law. Institutional accountability, not personality rule, is the foundation of governance maturity.

Africa’s future will not be secured by replacing one dependency with another, nor by elevating any foreign power to messianic status. True Pan-Africanism is not the echoing of external talking points; it is the deliberate construction of institutions that serve African citizens.

Russia itself is not inherently a threat. But the uncritical adoption of its current governance model, particularly in fragile states with histories of authoritarianism, risks deepening political stagnation and security deterioration.

Nigeria, as Africa’s largest democracy, bears a responsibility, not to antagonise any nation, but to champion democratic resilience across the continent. The real question is not whether Russia can offer Africa a partnership. It is whether Africa is prepared to interrogate the governance model embedded in that partnership.

If Africa’s ambition is prosperity, stability, and dignity for its people, the path forward must begin and end with accountable governance.

Oumarou Sanou is a social critic, Pan-African observer and researcher focusing on governance, security, and political transitions in the Sahel. He writes on geopolitics, regional stability, and African leadership dynamics. Contact: sanououmarou386@gmail.com

Interrogating the Russian Model in Africa

International

UK Abolishes Visa Stickers for Nigerians, Introduces Mandatory eVisas from Feb 25

UK Abolishes Visa Stickers for Nigerians, Introduces Mandatory eVisas from Feb 25

By: Michael Mike

The United Kingdom will from 25 February 2026 stop issuing physical visa stickers to Nigerian travellers, replacing them entirely with digital eVisas in what officials describe as a major overhaul of the country’s immigration system.

Announcing the change in Abuja, UK Visas and Immigration (UKVI) said all new Visit visas granted to Nigerian nationals will now be issued electronically, marking a decisive step in the UK’s transition to a fully digital border regime.

Under the new system, successful applicants will no longer receive a vignette pasted into their passport. Instead, they will access proof of their immigration status online through a secure UKVI account.

The British government stressed that the application procedure itself remains unchanged. Nigerian applicants must still complete the standard online process, attend a Visa Application Centre to submit biometric data and meet all existing eligibility requirements. The only adjustment is the format in which the visa is delivered.

Authorities clarified that Nigerians currently holding valid visa stickers will not be affected by the new policy. Their visas will remain valid until expiration and do not require replacement solely because of the transition.

British Deputy High Commissioner in Abuja, Gill Lever, said the move is designed to simplify travel while enhancing security.

“We are committed to making it easier for Nigerians to travel to the UK. This shift to digital visas streamlines a key part of the process, strengthens security and reduces reliance on paper documentation,” she said.

According to UKVI, the eVisa system is expected to shorten processing timelines since passports will no longer need to be retained for visa sticker endorsement. Travellers will also be able to view and manage their immigration status online at any time, from anywhere.

Officials highlighted the added security benefits of the digital format, noting that unlike physical stickers, eVisas cannot be lost, stolen or tampered with. The system is also designed to provide real-time verification of immigration status.

Once a visa is approved, applicants will be required to create a free UKVI account to access and share their eVisa details when necessary.

The policy shift signals a broader modernization of the UK’s border management framework and places Nigerian travellers among the first groups to experience the fully digital visa rollout.

For frequent travellers, students and business visitors, the reform represents a significant procedural change—one that replaces paper documentation with an online immigration record as the new standard for entry clearance into the United Kingdom.

UK Abolishes Visa Stickers for Nigerians, Introduces Mandatory eVisas from Feb 25

-

News2 years ago

News2 years agoRoger Federer’s Shock as DNA Results Reveal Myla and Charlene Are Not His Biological Children

-

Opinions4 years ago

Opinions4 years agoTHE PLIGHT OF FARIDA

-

News11 months ago

News11 months agoFAILED COUP IN BURKINA FASO: HOW TRAORÉ NARROWLY ESCAPED ASSASSINATION PLOT AMID FOREIGN INTERFERENCE CLAIMS

-

News2 years ago

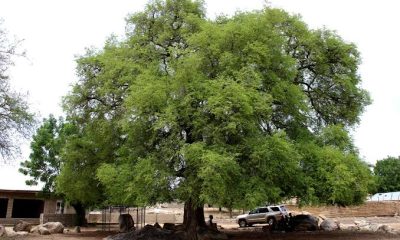

News2 years agoEYN: Rev. Billi, Distortion of History, and The Living Tamarind Tree

-

Opinions4 years ago

Opinions4 years agoPOLICE CHARGE ROOMS, A MINTING PRESS

-

ACADEMICS2 years ago

ACADEMICS2 years agoA History of Biu” (2015) and The Lingering Bura-Pabir Question (1)

-

Columns2 years ago

Columns2 years agoArmy University Biu: There is certain interest, but certainly not from Borno.

-

Opinions2 years ago

Opinions2 years agoTinubu,Shettima: The epidemic of economic, insecurity in Nigeria