News

The Sahel Descent: Illusion of Russian Mercenaries-Lessons for Nigeria and Africa

The Sahel Descent: Illusion of Russian Mercenaries-Lessons for Nigeria and Africa

•Why Wagner betrayed Africa—and what Nigeria must learn fast.

•Russia’s mercenaries promised security. They delivered bloodshed, racism, and catastrophic failure. Now the jihadists are at the gates—and Nigeria could be next.

By Oumarou Sanou

Bamako is burning—again, and the African Union, the regional body tasked with promoting peace and security, is panicking. The capital of Mali, once a proud symbol of West African resilience, now teeters on the brink of collapse, not from foreign invasion but from jihadists who have outlasted coups, crushed alliances, and exposed the hollowness of the “sovereign security” promised by military juntas and their Russian backers. What began as a bold pledge to “restore stability and reclaim dignity” has descended into chaos, bloodshed, racism, and betrayal—the tragic proof that mercenaries cannot buy peace, and juntas cannot govern by force. The Sahel’s descent is not just Mali’s tragedy—it is a warning to Nigeria and the entire region.

When Mali’s coup leaders expelled French and UN forces and turned to Russia’s Wagner Group in 2021, they sold their citizens a dangerous illusion: that imported soldiers of fortune would succeed where legitimate institutions had failed. Three years later, the results are catastrophic. Jihadist groups are advancing toward Bamako, civilians are dying in record numbers, and the mercenaries once paraded as “liberators” have turned Mali’s soil into a graveyard of false hope.

According to conflict monitors, nearly 3,000 civilians have been killed since Wagner’s arrival—many at the hands of their supposed protectors. Entire communities have been wiped out, markets torched, and villages erased under the pretext of “counterterrorism operations.”

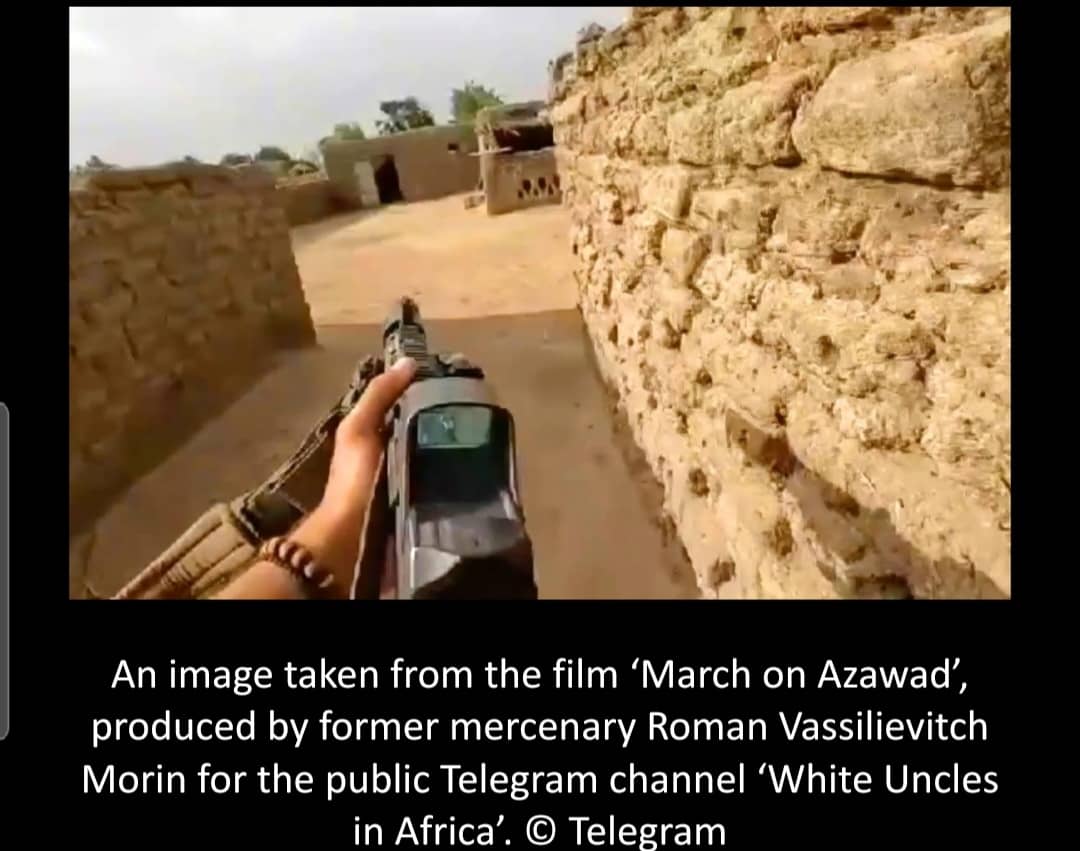

The recently leaked documentary March on Azawad—a chilling self-portrait of Russian mercenaries—reveals the futility and racism embedded in their operations. Wagner veterans, now safely back in Russia, describe Malian soldiers as “cowards” and “thieves,” mocking the very people they were paid to defend. Their disdain echoes the systemic racism of Russian society, where ethnic minorities are treated as expendable cannon fodder. These mercenaries, steeped in bigotry and violence, brought to Africa not solidarity, but supremacy — the same dehumanising ideology that drives their atrocities in Ukraine, Libya, and now the Sahel.

The brutality Wagner displays toward African civilians is not aberrational—it is a feature, not a bug. These mercenaries carry to Africa the same racism they practice at home against ethnic minorities in Russia’s own territories. In Chechnya, Dagestan, and other non-Russian regions, minorities face systemic discrimination, violence, and marginalisation. When these fighters arrive in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger, they bring that contempt with them.

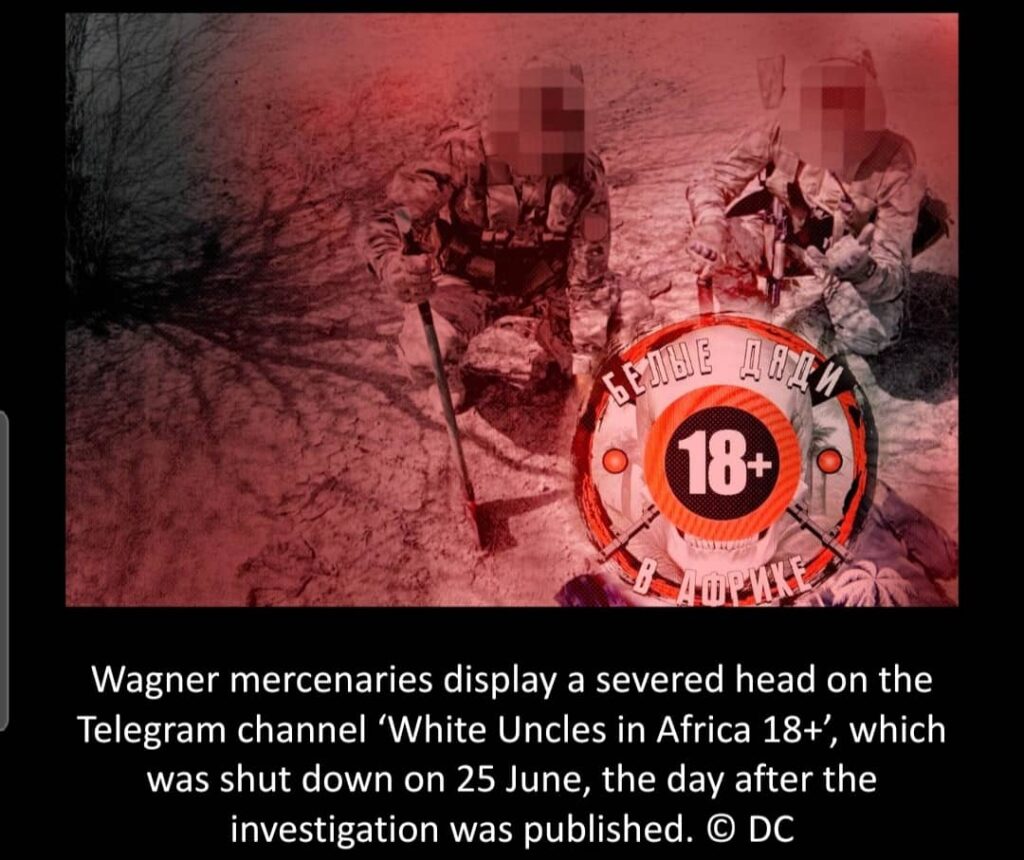

Their crimes are well-documented. In Moura, central Mali, at least 500 civilians were massacred in a single operation in March 2022. Men were executed, women assaulted, and children mutilated—atrocities gleefully shared in private Wagner Telegram channels like “White Uncles in Africa +18”, where mercenaries celebrated their brutality with the depraved language of white supremacy. To them, African civilians and terrorists were indistinguishable—both expendable, both “sand people.” This is not counterterrorism. It is a campaign of dehumanisation.

Behind Wagner’s bloody record lies a simple motive: profit. The mercenaries did not come for Pan-African solidarity; they came for gold. Mali pays Wagner not only in cash but in mineral concessions—trading sovereignty for survival. One mercenary admits in the documentary that recovering and seizing gold mines was part of their operational “successes.” They looted everything: motorcycles, trucks, excavation equipment. Mali’s resources now flow to Moscow, while its people bleed in silence.

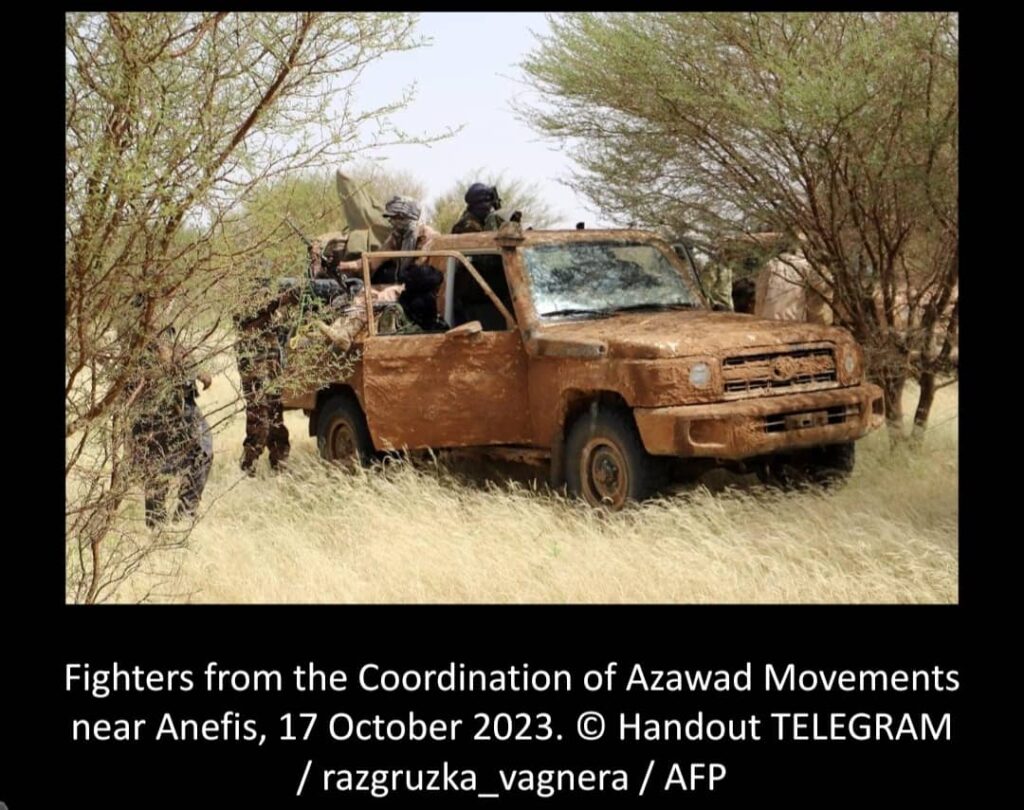

What began as a “security partnership” quickly degenerated into an extractive occupation. Wagner’s recklessness and racial contempt alienated communities, fractured the Malian army, and emboldened jihadists. The July 2024 defeat at Tinzawaten, where 84 Russian mercenaries died alongside dozens of Malian troops, was not an exception—it was the predictable outcome of arrogance and incompetence. The withdrawal of Wagner and its rebranding as “Africa Corps” in 2025 has done little to stem the tide. Today, Bamako stands at the edge of jihadist capture.

The implications for West Africa—and especially Nigeria—are profound. Insecurity in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger does not remain contained; it metastasises. Jihadist groups like JNIM and ISGS have expanded their operations southward, exploiting porous borders, ungoverned spaces, and weak regional coordination. Refugees fleeing the Sahel are already straining Nigeria’s northern communities, while arms trafficking and extremist propaganda infiltrate the hinterland and towns. The possible fall of Bamako would open another corridor of terror stretching from the Maghreb to the Gulf of Guinea—an arc of instability that could engulf the entire subregion. This underscores the need for robust international collaboration in addressing the crisis.

Nigeria must heed this warning with urgency and clarity.

Unlike Mali’s junta, Nigeria has—so far—resisted the temptation of outsourcing its sovereignty to foreign mercenaries. This path has been slow, imperfect, and riddled with challenges, but it is fundamentally different. They have so far relied on their national forces, accountable—however imperfectly—to the constitution, and also engage regional structures such as ECOWAS and the Multinational Joint Task Force, a collaborative security initiative involving several African countries. Nigeria collaborate internationally while preserving national agency.

This is the only sustainable route to lasting peace.

But Nigeria must not grow complacent. Their military architecture still faces serious weaknesses—underfunding, corruption, rights abuses, and inadequate intelligence coordination. Reform is not optional; it is urgent. The country needs a people-centred security strategy built on trust, legitimacy, and professionalism. That means investing in their troops, strengthening community-based intelligence, enhancing regional cooperation, and tackling the root causes that jihadists exploit: poverty, exclusion, and bad governance.

For the rest of Africa, the lesson from the Sahel is brutally clear: mercenaries do not save nations—they strip them bare. Authoritarian juntas that cloak repression in “sovereignty” only invite further collapse. Imported guns or imperial contracts cannot secure Africa’s stability. It must be built through accountable institutions, regional solidarity, and the courage to confront our internal failings head-on.

Mali’s tragedy is a mirror. It shows what happens when desperation replaces strategy, and when sovereignty becomes a slogan for repression. The fall of Bamako—if it happens—will not just be Mali’s failure; it will be a continental warning. Nigeria must learn, act, and lead—because in today’s Sahel, those who chase shortcuts to security end up losing both peace and power.

Oumarou Sanou is a social critic, Pan-African observer and researcher focusing on governance, security, and political transitions in the Sahel. He writes on geopolitics, regional stability, and the evolving dynamics of African leadership. Contact: sanououmarou386@gmail.com

The Sahel Descent: Illusion of Russian Mercenaries-Lessons for Nigeria and Africa

News

Zamfara: Troops neutralise terrorist, recover arms in Shinkafi LGA

Zamfara: Troops neutralise terrorist, recover arms in Shinkafi LGA

By Zagazola Makama

Troops of the 1 Brigade of the Nigerian Army operating under Operation FANSAN YANMA have neutralised a suspected terrorist and recovered arms during an offensive operation in Shinkafi LGA.

Security sources told Zagazola Makama that the operation was carried out on March 13 by troops of CT 5, who launched a deliberate clearance mission targeting terrorist camps located at Tubali and Zangon Danmaka.

The sources said the operation followed credible intelligence on the presence of armed bandits and other criminal elements using the locations as operational hideouts.

During the operation at Tubali, troops made contact with the suspected terrorists and engaged them in a brief gun battle, forcing the criminals to flee into nearby forested areas.

“During the engagement, one terrorist was neutralised, while others escaped with possible gunshot wounds,” the source said.

Following the encounter, troops conducted exploitation of the area and recovered one AK-47 rifle, a magazine containing two rounds of 7.62mm special ammunition, and a motorcycle believed to belong to the fleeing terrorists.

The recovered items were secured by the troops while further search operations were carried out around the camp to ensure that no other threats remained in the vicinity.

The sources added that when troops advanced to Zangon Danmaka, no contact was made with terrorists as the suspects were believed to have fled the area ahead of the troop arrival.

However, troops maintained dominance in the general area while conducting further patrols and surveillance operations aimed at preventing the terrorists from regrouping.

Zamfara: Troops neutralise terrorist, recover arms in Shinkafi LGA

News

Troops arrest suspected ISWAP spy in Kanama, Yobe

Troops arrest suspected ISWAP spy in Kanama, Yobe

By Zagazola Makama

Troops of 159 Battalion in collaboration with members of the Civilian Joint Task Force have arrested a suspected spy linked to terrorists operating in the North-East in Kanamma Yobe state.

Security sources told Zagazola Makama that the suspect, identified as Malam Fantami, a native of Dikwa was apprehended during a security operation by troops deployed in the area.

The sources said the suspect was intercepted following credible intelligence indicating that he might be working as an informant for terrorists affiliated with the ISWAP.

According to the sources, items recovered from the suspect at the time of his arrest included a mobile phone, a smart watch, prayer beads, a motorcycle key, and a cash sum of ₦7,000.

Preliminary examination of the suspect’s mobile phone by security personnel reportedly revealed several suspicious materials, including photographs of motorcycles, large sums of cash, AK-47 rifles and other items believed to be linked to terrorist activities.

“The discovery of these materials has raised serious suspicion about the suspect’s role as a possible logistics informant or intelligence asset for insurgent elements operating in the region,” the source said.

The suspect is currently in military custody, where he is undergoing further interrogation to determine the extent of his involvement with terrorist networks and to identify possible collaborators.

The military high command said the arrest forms part of ongoing counter-terrorism efforts by troops in the North-East aimed at dismantling the intelligence and logistics networks that support insurgent operations.

Kanama, located in Yunusari Local Government Area of Yobe State near the border with Niger Republic, has remained an important corridor frequently exploited by insurgent groups for movement and supply activities.

Troops arrest suspected ISWAP spy in Kanama, Yobe

News

Troops repel ISWAP attack in Bita, Borno

Troops repel ISWAP attack in Bita, Borno

By: Zagazola Makama

Troops of Operation HADIN KAI successfully repelled an attack by terrorists suspected to be members of ISWAP in Bita area of Borno state following a fierce overnight encounter.

Security sources said the attack began at about 1:09 a.m. on Saturday, when the insurgents launched a coordinated assault on troops of the 26 Task Force Brigade deployed in the Bita axis.

According to the sources, the terrorists attempted to overwhelm the troops’ position but were met with stiff resistance from the soldiers who engaged them in a sustained gun battle.

“In a decisive and coordinated operation, gallant troops of Operation Hadin Kai launched a simultaneous land and air assault on terrorist positions in Bita in the early hours of today,” the source said.

The coordinated response involved ground troops engaging the insurgents while aerial support conducted precision strikes and surveillance over the battlefield, forcing the attackers to retreat.

The intense engagement compelled the terrorists to withdraw towards their enclaves after suffering heavy pressure from the combined land and air assault.

Following the withdrawal of the insurgents, troops immediately commenced exploitation operations to pursue fleeing elements of the terrorist group and prevent them from regrouping.

Troops repel ISWAP attack in Bita, Borno

-

News2 years ago

News2 years agoRoger Federer’s Shock as DNA Results Reveal Myla and Charlene Are Not His Biological Children

-

Opinions4 years ago

Opinions4 years agoTHE PLIGHT OF FARIDA

-

News11 months ago

News11 months agoFAILED COUP IN BURKINA FASO: HOW TRAORÉ NARROWLY ESCAPED ASSASSINATION PLOT AMID FOREIGN INTERFERENCE CLAIMS

-

News2 years ago

News2 years agoEYN: Rev. Billi, Distortion of History, and The Living Tamarind Tree

-

Opinions4 years ago

Opinions4 years agoPOLICE CHARGE ROOMS, A MINTING PRESS

-

ACADEMICS2 years ago

ACADEMICS2 years agoA History of Biu” (2015) and The Lingering Bura-Pabir Question (1)

-

Columns2 years ago

Columns2 years agoArmy University Biu: There is certain interest, but certainly not from Borno.

-

Opinions2 years ago

Opinions2 years agoTinubu,Shettima: The epidemic of economic, insecurity in Nigeria