Feature

General Lagbaja, the Nigerian Army, and the myriads of unfinished businesses

General Lagbaja, the Nigerian Army, and the myriads of unfinished businesses

By: Bodunrin Kayode

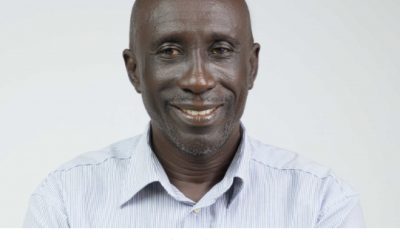

If there is any personnel in military uniform in Nigeria today who would be extremely devastated about the death of General Lagbaja, it is the Chief of the defense staff General Chris Musa. He obviously had a very smooth working relationship with the late Army Chief before his demise. General Musa is one of the few military Commanders who have swallowed the bitter taste of asymmetric warfare in the battle fields of “Hadin Kai” and the entire country. He is a warrior whose patriotism General Lagbaja emulated.

Lieutenant General Taoreed Lagbaja would be sorely missed by all his colleagues and men whom he walked with through the valleys of torments and came out in one piece. They will never forget another fine General who often led his troops from the front following after the pattern of predecessors like Generals Tukur Buratai, Lamidi Adeosun, Chris Musa and many other warriors who have passed through this theatre. Even at the 7 division level we had warriors like General Abdulsalam Abubakar who have since left the theatre for another front of banditry torment at the 3, division of the Nigerian Army and Brigadier General Abubakar Haruna current General Officer Commanding (GOC) of the 7 division who had served the city of Maiduguri as Garrison Commander before now. They have all crossed his path at one operation or the other as ordered by army headquarters(HQ).

Lagbaja’s battles against Boko Haram

For the one decade I have worked within the “Hadin Kai” war theatre, I have seen and reported the activities of many Army Generals coming and leaving their sector posts at close range. As a matter of fact, they are too many to mention who came and left at a time we needed them most like Major Generals Abdulkalifa Ibrahim who is now the infantry Chief of the Army and Ibrahim Ali holding fort at the Multinational joint task force (MNJTF) HQ. From the kinetic proactive Commanders, to those who spend more time in the non kinetic realms than in the battle field. All directed to end the insurgency with their strengths and weaknesses as we reporters hear from the interpretation of the residents who judge their respective fighting prowesses. In all these, I have only encountered Lagbaja as the Army Chief coming on operational visits which may not be regarded as close range but close enough to sense the signs of the tides and his body languages which was always that of a warrior screaming “end this war” to his troops. Military sources hinted this reporter that in all his command positions he held under the days of “Lafia Dole” interacting between sector one and three even around the brutal mine fields of Baga, he had always maintained the same pattern of motivation of his troops by leading from the front and not expecting anything special for doing the job. His style was obviously more of less talk and more action. I never had that close working relationship with lagbaja as I had with others like Generals Koko Isoni, Rogers Nicholas, Ibrahim Attahiru, Faruk Yahaya, Ibrahim Ali, Nura Mayirenso Saraso and many others but from a distance and judging from what my colleagues used to report about him at the Bernin Gwari front, he was indeed a warrior. He cared about his troops which is why immediately he assumed duty he started fighting for increased welfare for them. It is only a general who have had keen encounters with his troops that will know exactly what their challenges are. And Lagbaja knew their challenges.

Efforts by the military to maintain sanity in the war theatre

A lot of efforts have been channeled into the maintenance of peace and sanity in the Hadin Kai war theatre and history will remember Taoreed Lagbaja as one of the few Generals who faced fire at the frontline in this theatre before moving to others to fight for his country. From General’s Buratai to Lamidi Adeosun to Victor Ezegwu to many others like Chris Musa who got double promotion and today he is the Chief of the entire Nigerian military. They all tried their best to make their impacts before leaving. Most of them left as warriors except for Ibrahim Attahiru who had to contend with the shortest and bloodiest attacks here before leaving. On his movement to headquarters, he was later made the Army Chief but lost his life in a plane crash making his reign an equally short lived one. Attahiru it was who actually changed the name of “Lafia Dole” to Hadin Kai to suite the exigency of that time.

Lagbaja’s meteoric promotion from GOC to Army Chief

No General in recent times has being promoted to become Chief from outside “Hadin Kai” except Lagbaja who had passed through the theatre as an unsong warrior. Of course Hadin Kai had become a big bone in the throat of the military and it was obvious that only warriors from this theatre that could be made Chief of the Nigerian Army. If one did not understand the dynamics of the asymmetric warfare down here, one’s ability to review operational strategies and change tactics would be highly impaired. However, General Lagbaja’s case was unique which is why his own elevation never came from this theatre as the likes of General Faruk Yahaya who followed the footsteps of Attahiru. Rather he was busy leading from the front as General Officer Commanding GOC the one division of the Army at the Kaduna theatre axis when he was told to drop his weapons and prepare to propound and approve policies for tactical warfare at the Army headquarters as the first Army Chief for President Bola Tinubu. In other words, while troops were busy taking out the enemies in Sambisa and the Lake Chad region from this axis Lagbaja was leading from the front in the north west theatre where he was the GOC 1 division of the Nigerian Army. It is from this point that he rose to the rank of Army Chief. Even as army chief he still maintained his style of seeing things for himself. Feeling the pulse of his troops and impacting his style on them.

“He led from the front and was always ready to take the bullet for his troops.” Said Chiroma a private soldier who fought along side him in the Lafia Dole theatre. One thing I have learnt inside the Hadin Kai war theatre as a defacto defense correspondent is that troops always celebrate their Generals or Commanders who led from the front. Lt General Taoreed Lagbaja was a highly celebrated officer who had many dreams for a modern Nigerian Army. His humility never allowed him to adorn himself with all his medals of a true warrior because they were so many.

His introduction of the first air platform components for the Army was a huge success for the administration of President Bola Tinubu who wanted to prove his mettle at the management of the security sector. Lagbaja had received two Bell UH-1H ‘Huey’ helicopters registered as NA 010 and NA 011 in June this year. With that introduction the Army has stepped up its operational efficiency especially in dangerous sections of the fight against terrorism in the North East and Western flanks of the country. Too many times the air force had delayed in giving them the spontaneous service they used to require. With the development of the aviation component of the Army, troops will now be well protected whenever they need to break through short range barriers. This new development will equally reduce the prevalence of erroneous mistakes sometimes on own troops in any of the troublesome theatres.

Motivational speaker and press ups exercises

The passage of General Lagbaja to the great beyond is not only a huge loss to the Nigerian army, it is also a loss to the entire country. He was a great motivator to his troops wherever he went to.

Seeing that his troops lacked motivation in certain instances, he had personally gingered them up in press up exercises while observing their faces and body languages. Breaking protocols at times to discuss with troops over their challenges. He was not heavily built and kept an average tummy which spoke volumes to those officers who had massive tummies hindering them in their movements. He was an obviously big time dreamer with lots of thoughts for his people.

Goodbye General Lagbaja

Sadly for me I only had one instance to say hello to this great General who some of us felt was a bit media shy and may not like any sudden form of interaction with us especially our electronics colleagues who sometimes are unable to read body languages to know when not to cross some lines. He was shy initially but as he kept coming to the theatre, his countenance improved. His case was a bit better than General Faruk Yahaya who kept journalists at arms length like some dangerous irritants while in the theatre but adjusting when he became the Chief. All thanks to the Army spokesman Major General Onyema Nwachukwu, they always fall in line to accept the media as Co-fighters against evil when they become chiefs. Nwachukwu is also an acknowledged pen warrior who did so much in moulding these Generals to understand that the army is not part of the secret service so they always opened up after they hit the ground running.

Ambushing Lagbaja

Lagbaja had arrived Maiduguri with his defense Chief General Chris Musa and they had done their usual operational reviews inside the hall of Hadin Kai HQ while we milled around pinging our phones or snacking as we wait for them to tell us why the war still lingers. They came out for group pictures and interactions with the media which is the style of General Musa before they took off to see wounded troops in the hospital. Then I cornered him as he ruminated over what may have happened inside the hall. Some of them had loosened up but not Lagbaja. He was always at red alert. As a matter of fact, while the interaction continued he had a cold stare common with the ogas when their boys have not met the yard stick they had given them. As if he should come down and lead them through the valleys of the shadow of death. That “I fear no evil” sight of a warrior. I was taking aback a bit and hesitated slightly. But I then introduced my experience to engage him looking straight into his eyes and retorted: “Good day General” I said to him. He looked at me with that windless stare that would not allow you to construct his mind from his face. I later learnt that is his trade mark as a toughie when on duty. He gave me a nod. Clear sign don’t ask further questions. I smiled in my mind and said this one is really a tough one. And went further, “I wish you the best General and be sure that we will continue to fight with our pens along side your troops at this side of the theatre”. He gave a second nod of approval and walked off like one of his mentors in the American war college where he trained. It was time to go so his ADC who had kept a distance went tugging along with the General into the air conditioned bus waiting for the entourage to embark and finish the tour. It was a chanced meeting and I enjoyed it though. Later that month, I would hear him in another theatre commending the gentlemen of the pen for fighting along with his troops. He obviously have done his best being the Chief of a badly overstretched Army. It’s up to his predecessor to keep the flag flying by clearing all the terrorists bragging around the country and increasing the army alone to at least 100,000 men and officers before the end of the first term of the Commander in Chief President Tinubu. The Army, Airforce and Navy should not be less than 500,000 officers and men by 2034. It’s practicable if the new Chief in conjunction with defense and the National Youth Service Corp creates a corp of reservists which can always supply the main stream as it is done in Israel and many other countries. We cannot continue to allow terrorists to be embarrassing and humiliating the biggest economy on the African continent except if it is for a purpose.

Smoking these people out once and for all does not mean that there would not be theatres for troops to practice their trades. There are many theatres of war they can be shipped to outside the country when our borders are cleared and sealed. These are the tasks before the new Army chief. Nigerians expect better deals in terms of security and Lagbaja understood that and was deliberately going after the well-being of the nation.

He will be enjoying his peaceful sleep till we meet to part no more. May the Lord console the entire family of the Lagbaja’s especially his uncle who is going to live the rest of his old age in regrets that his nephew was buried before him which to him is a deep stab in his fragile heart. My condolence too goes to the Commander in chief of the armed forces of Nigeria President Bola Tinubu.

General Lagbaja, the Nigerian Army, and the myriads of unfinished businesses

Feature

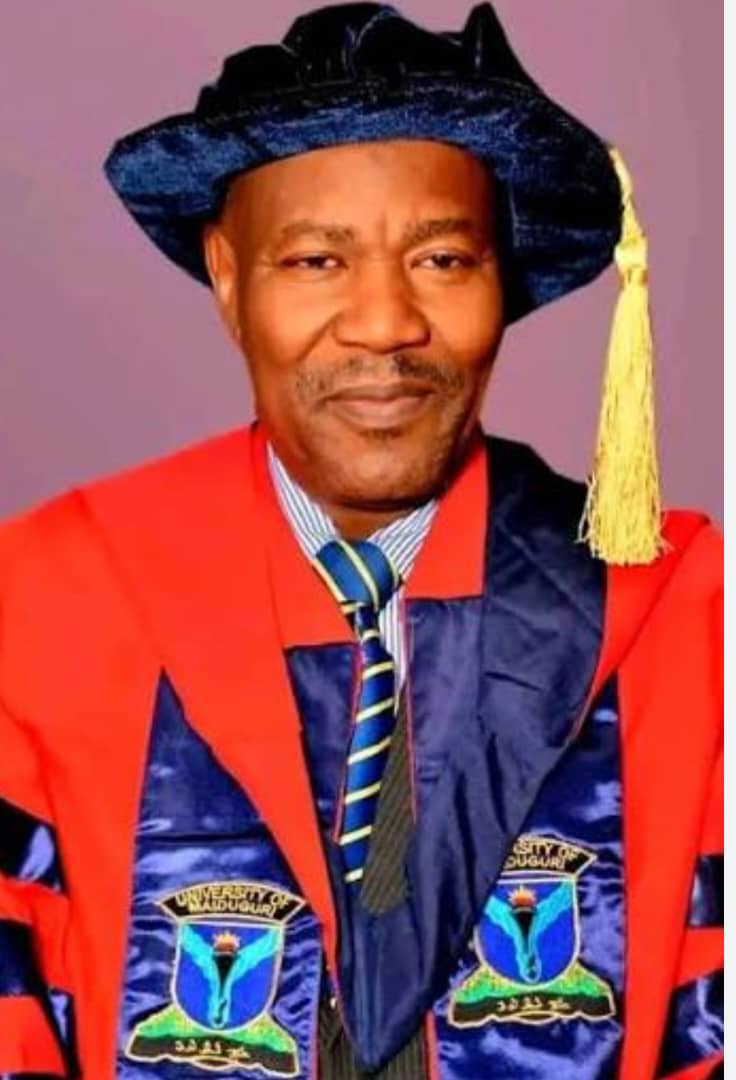

Celebrating the Legendary Malam Umaru A. Pate

Celebrating the Legendary Malam Umaru A. Pate

By Hamza Idris

Tuesday, February 10, 2026, marks his last day as the Vice Chancellor of the Federal University Kashere, Gombe State.

The world saw him smiling as he bade farewell to the university community, as captured in stories and tributes by those who know him, and carried by multiple print and broadcast media platforms.

In journalism, his tenure at Kashere is what is aptly described as a success story, and his departure can fittingly be termed a glorious exit.

Many of us call him Malam as a mark of reverence because we find it very difficult to look into his eyes and call him Prof. The reason is simple: by the Grace of Allah, he made many of us what we are today.

Malam Pate was not alone in shaping our journey while we were at the Department of Mass Communication, University of Maiduguri (UNIMAID). We also had Malam Danjuma Gambo, Malam Abubakar Muazu, Malam Alhaji Musa Liman (late), Malam Mohammed Gujbawu (late), Malam Mustapha Mai Iyali, Malam Nasiru Abba Aji, Mr Udomiso, Mr Nwazuzu, Malam Musa Konduga, Malam Hassan A. Hassan, Madam Ramla (late), Malam Musa Giwa (late), and Malam Alabura (late). I hope I have got all the names correctly, among others. They all impacted our lives positively, and we remain eternally grateful.

But today is Malam Pate’s day, and HERE IS MY STORY ABOUT HIM, which I have told again and again at different fora, and which I am glad to tell once more today.

The best way to tell his story is by using the parable of the blind men and the elephant. Here it is:

Once upon a time, a group of blind men heard that a strange animal called an elephant had been brought to their village. None of them had ever encountered one before, so they decided to learn what it was like by touching it.

Each blind man approached the elephant from a different side.

The first man touched the elephant’s leg and said, “An elephant is like a pillar—strong and firm.”

The second man touched the tail and said, “No, the elephant is like a rope, thin and flexible.”

The third man touched the trunk and declared, “You are both wrong. An elephant is like a thick snake.”

The fourth man touched the ear and insisted, “An elephant is like a fan, wide and flat.”

The fifth man touched the tusk and said confidently, “The elephant is like a spear, hard and sharp.”

Soon, the blind men began to argue. Each believed he alone was right and that the others were wrong, even though each had touched only one part of the elephant.

A wise man who was passing by listened to their argument and said, “All of you are right, and all of you are wrong. Each of you has touched only a part of the elephant. Because you cannot see the whole thing, you think your part is the entire truth.”

The blind men fell silent, realizing that the truth was greater than any single perspective.

This parable clearly tells us the man Malam Pate. You only tell what you know about him but to him, all his proteges are his favourites.

After we graduated from UNIMAID in 2002 and completed our NYSC, I continued with the job that was available at the time—teaching.

In 2005, Daily Trust newspaper had a vacancy in Yola, Adamawa State, and the then Bureau Chief, Malam Abdullahi Bego (also an alumnus of Mass Communication, UNIMAID and currently the Commissioner of Information in Yobe State), was tasked with the responsibility of getting the right person and he reached out to Malam Pate to nominate anyone he felt could serve as State Correspondent in Adamawa.

Malam Pate then contacted one of our classmates, Amina Mohammed. However, for some obvious reasons, Amina did not take up the job. Instead, she informed Malam Pate that I was yet to secure a proper job in line with what I studied at the university.

He asked her to tell me to call him, which I did. Amina currently works at the information unit of Federal Medical Centre, Yola. I remain eternally grateful to her.

Malam Pate then linked me up with Malam Bego after vouching for my integrity and passion for the job—and that was it. I was offered automatic employment as a Reporter and Researcher—no interview, nothing.

This was over 20 years ago. Only God knows the number of people who secured jobs through Malam Pate. The mere mention of his name clears the pathway. It is very unlikely to visit five establishments in Abuja and any other state, provided they have a public affairs directorate, without seeing someone that got there through Malam.

It is very unlikely to visit any media organisation in Nigeria (newspaper, radio or television) without coming in touch with someone that benefited from Malam through training or mentoring. It is also very unlikely to visit any faculty or department of mass communication or journalism in any university or polytechnic in Nigeria, without seeing someone who studied under Malam, or benefitted from his supervision or mentorship in the course of his studies. He is a real benefactor.

Malam Pate is one of the guarantors on my CV. The other two are my former Editor-in-Chief, Malam Mannir Dan-Ali, and Malam Bego. Over the past 20 years, I have secured dozens of fellowships and trainings, both at home and abroad, largely because their names appear on my résumé. I also presented endless papers at high profile gatherings, all because some good people told others that yes, you can do it.

Ahead of the World Press Freedom Day in 2016 or thereabouts, Malam Pate called and asked me to write about my experience covering the Boko Haram crisis under the theme: Professionalism and Risk Management in the Reporting of Terror Groups and Violent Extremism in North-East Nigeria, How Journalists Survived to Report.

He, on his part, wrote the contextual aspect of the topic, shared the byline with me—even though he did the bulk of the work—and went on to present the paper in Helsinki, Finland.

Gladly, the same paper has found its way into at least two books, including Assault on Journalism, edited by Ulla Carlsson and Reeta Poythari, Nordicom, University of Gothenburg, Sweden (2017); and Multiculturalism, Diversity and Reporting Conflict in Nigeria, Evans Brothers (Nigeria Publishers) Limited, which he edited together with Professor Lai Oso (2017).

The paper has also been cited in many MSc and doctoral theses, both in Nigeria and around the world.

Indeed, Malam Pate is a father figure to many of us. Kindly share your experience in the comment section so that we can collectively celebrate this enigmatic figure.

Malam, as you open another chapter in your life after recording this milestone at the Federal University Kashere, may Allah continue to be your driving force, granting you good health and amity as you tirelessly change the face of journalism teaching and practice.

Celebrating the Legendary Malam Umaru A. Pate

Feature

Economic reforms: How did President Tinubu uniquely reshape Nigeria’s economy?

Economic reforms: How did President Tinubu uniquely reshape Nigeria’s economy?

By: Dr Abolade Agbola

In a few months, the economic reforms of the government of President Tinubu will be three years old, while the government will be on the last lap of its four-year first-term mandate.

The President’s statement at his inauguration on the 29th May 2023, that “the fuel subsidy was gone,” ushered in a series of reforms that reshaped the economy. Two weeks after the President’s inauguration, the Central Bank unified the multiple exchange rates on 14th June 2023 and transitioned from a rigid, multi-layered exchange rate system to a unified, “willing buyer-willing seller” managed float regime.

The Presidential Committee on Fiscal Policy and Tax Reforms was constituted in July 2023 to draft a new tax and fiscal law. In March 2024, the Central Bank announced a new threshold for bank capital, requiring banks to increase their minimum share capital by the March 31, 2026, deadline to strengthen the financial system against impending economic shocks following the reforms and support the nation’s economic growth target of $ 1 trillion in GDP by 2030. Nigeria has had several foreign exchange market reforms, but the most profound ones are the transition from the Import licensing scheme to the Second-Tier Foreign Exchange market in 1986, following the deregulation and liberalization of the economy, and the massive devaluation of the currency in 1994. The uniqueness of the 2023 reforms lay in their timing, at the dawn of the administration, and in complementary policies such as the floating of the Naira following the abolition of multiple exchange rates, thus allowing the market to achieve equilibrium simultaneously in the pricing of petrol and the Naira.

The fuel subsidy removal led to a price increase for petrol from N200 per litre in May 2023 to between N1,200 and N1,300 per litre in early 2025. The floating of the Naira and unification of multiple exchange rates led to the currency’s massive devaluation from N460: $1 on 29th May 2023 to N1,700: $1 by November 2024. The post-subsidy removal and Naira floatation in the economy led to high inflation and a decline in household consumption. According to the World Bank, 56% of Nigerians (over 113 million people) living below the poverty line in 2023 are projected to reach 61% (139 million) by 2025.

Today, the Naira is stabilizing at about N1,400: $1, while petrol has fallen to about N880 per litre, and inflation has receded to 15.15%, with prospects of getting to a single digit before the end of 2026. A single-digit inflation rate will take a substantial number of people out of poverty as the mystery index declines alongside the receding inflationary spiral, as policies that foster job creation, reduce price volatility, and stimulate economic growth are implemented.

Nigeria was on the brink of economic collapse in 2023. Most of the sub-nationals were unable to pay salaries. There was no budget for fuel subsidy from 1st June 2023. The external reserves of US$34.39 billion in May 2023 were barely adequate to finance 6.5 months of imports of goods and services and 8.8 months of imports of goods only. JP Morgan, a global financial institution, later claimed that the previous administration actually left Nigeria with a net reserve of $3.7 billion, rather than $34.39 billion. In May 2023, the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) had a foreign currency liability to foreign airlines of approximately $2.27 billion due to the airlines’ inability to repatriate their ticket sales revenue. Nigeria’s foreign reserves stood at $45.21 billion as of December 2025. In fact, the country experienced significant trade surpluses, with reports indicating around N6.69 trillion (Exports: N22.81tn, Imports: N16.12tn) as at the third quarter of 2025, driven by rising crude oil and non-oil exports, such as refined petroleum, despite some fluctuations and policy impacts, highlighting economic restructuring towards diversification.

Nigeria’s economic decline, which compelled the latest reforms, began in 2014, when crude prices began plummeting from their peak of $114 per barrel. Nigeria had two recessions in 4-year intervals, the 2016 recession, when the price of crude oil fell to $27 per barrel due to a U.S. shale oil-inspired glut. The other recession in 2020 was a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, when crude oil prices dropped to $17 per barrel amid worldwide lockdowns aimed at containing it. The economy was rebounding in 2022 when the Russia-Ukraine war disrupted the global commodity supply chain and triggered another round of economic crises.

The government was reluctant to depreciate the Naira in response to economic realities, given its populist and leftist inclinations. The consequence was the near collapse of the economy by the time the 2023 elections were held. The government borrowed massively with the intent of spending its way out of the recession. Nigeria’s total public debt was N77 Trillion, or $108 billion, when President Tinubu was sworn in on the 29th May 2023.

The debt profile had risen to N160 trillion ($111 billion) by the end of 2025, a moderate growth given the significant depreciation of the currency and the vast improvement in the country’s fortunes in the past two years.

Nigeria had intermittently grappled with rent, creating multiple exchange rates since 1986, when the corrupt-laden import license scheme gave way to currency auctions using the Dutch auction method. In 1986, amid the crude oil price meltdown, Nigerians rejected the IMF loan after a debate instigated by the military to carry the people along with the options available at the time for addressing the nation’s economic crisis. The objective of the IMF/World Bank-backed policy was to diversify the oil-dependent economy, reduce imports, privatize state firms, devalue the Naira, and foster private-sector growth to combat worsening economic conditions, such as inflation and debt overhang. In 2023, at its zenith, the rent reached N300 for every dollar sold by the central bank, creating artificial advantages in the market and enabling a few to extract wealth without effort.

No wonder President Tinubu remarked while campaigning that if the multiple exchanges remain for one day after he is sworn in as President, it means he is benefiting from the fraud, and added, “God forbid.”

Fuel price regulation started with the Price Control Act of 1977. The fuel subsidy was introduced around 1986, when we designated fuel stations into two categories. The station that sells to commercial vehicles offers subsidized prices, while the one that sells to private vehicles charges market rates. The arrangement collapsed, and the subsidy regime crept in.

Just as in 2023, Nigeria undertook a massive devaluation of the Naira and the removal of petroleum subsidies in 1994 during the era of General Sanni Abacha. The Naira was devalued from N22 to N80 per dollar in 1994, following the near-collapse of the economy after the annulment of the 12th June 1993 elections and a protracted period of low crude oil prices, which reached $16 per barrel in 1994. Almost simultaneously, the government removed some fuel subsidies and established the Petroleum Trust Fund, headed by the late President Muhammadu Buhari as Chairman, to manage projects funded by part of the removed subsidies.

According to CBN data, inflation rose from 57.03% in 1994 to 72.83% in 1995 due to the policy. The inflationary rate declined to 29.26% in 1996, and 8.52% in 1997, and 9.99% in 1998.

The reforms by President Tinubu in 2023, following the floatation of the Naira and the removal of the fuel subsidy, created a similar inflationary spiral. Inflation rate rose from 22.41% in May 2023 to 28.92% in December 2023, marking a 21-year high. The surge in inflation peaked at 34.80% by December 2024. The year-on-year inflation, however, declined to 15.15% by December 2025, indicating improving price stability as we approach the third year of the reforms.

There is no doubt that inflation will recede to single digits before the end of 2026 as the trigger factors (petrol prices and exchange rates) are now determined by market forces.

The reforms of President Tinubu in 2023 were unique in several ways. The courage to embark on both fuel subsidy removal and floatation of the Naira simultaneously at the dawn of the regime amounted to front-loading the expected and inevitable policy pains for gains that will manifest as the administration winds down its first term in office. What is certain after discounting for possible, unpredictable global headwinds such as commodity price volatility, the pandemic, climate change, and supply chain disruptions, to name a few, is that the economy will continue to improve as we approach the election year.

The trend will certainly play a key role in the 2027 elections. Unlike the 1994 subsidy removal and devaluation of the Naira, during which a portion of the fuel subsidy removal benefits was allocated to the Petroleum Trust Fund(PTF), the benefits of the 2023 policy actions were equitably and transparently shared among the three tiers of government, thereby strengthening the fiscal position of the federating units.

The inequitable distribution of PTF projects among the federating units remains a recurring point of criticism of the initiative. Monthly allocations to the 36 states and 774 local councils increased from roughly ₦458.81 billion in May 2023 to over ₦991 billion by June 2025, representing a 116% increase in some periods.

The improved FACC allocation to the states may be one of the reasons for the cordial relationship between most of the state governors and the federal government, as the states were able to execute many projects to fulfill their campaign promises.

Another unique foresight of the government in implementing the 2023 reforms is the recapitalization of banks to strengthen financial institutions, as the Naira weakens amid a spike in inflation. The massive devaluation of the Naira in 1994 led to a wave of bank failures some years later.

According to Central Bank reports, by 1998, 20 distressed banks had had their licenses revoked, with dire consequences for the economy. The 2024 banking recapitalization, ending March 2026, which gave banks a 24-month window to shore up their capital, was a masterstroke to strengthen the financial system, build stronger, more resilient banks to withstand Naira depreciation shocks, and foster sustainable economic growth and development.

The brand-new set of tax and fiscal laws delivered by the Presidential Committee on Fiscal Policy and Tax Reforms became operational on the 1st of January 2026.

The law aims to remove all barriers to business growth in Nigeria and further diversify the economy by enhancing its revenue profile, weaning the nation from reliance on crude oil export revenue.

The laws are to enhance revenue collection efficiency, ensure transparent reporting, and promote the effective utilization of tax and other revenues to boost citizens’ tax morale, foster a healthy tax culture, and drive voluntary compliance.

The government, after protracted negotiations with labour unions, reviewed the national minimum wage in July 2024, from ₦30,000 to ₦70,000 per month, to mitigate the impact of inflation, one of the most debilitating unintended consequences of the reforms. The government, in a proactive move, promulgated the National Minimum Wage Amendment Act 2024 to shorten the minimum wage review period from 5 years to 3 years, meaning that the next formal review is due in 2027.

There are several other projects and programmes aimed at repositioning the economy, such as the massive divestment of onshore oil assets in 2024 by International Oil Companies (IOCs) to indigenous Nigerian firms, which has increased crude oil production from 1.1mbarrel per day in 2023 to around 1.44million barrels per day (mbpd) in 2025. The speedy conclusion of the transfer deals and the rework of the assets is crucial to the actualization of the government’s target of daily production of 2.5m barrels per day in 2026 and the turnaround of the economy for another era of sustainable growth and development.

There is also the deployment of 2,000 high-quality tractors with trailers, ploughs, harrows, sprayers, and planters in 2025 as part of the government’s commitment to inject 2000 tractors annually to improve farming efficiency and reverse the poor mechanization of our farms. Nigeria, with a land area of 92m hectares, of which 34m hectares is arable, has less than 50,000 tractors, which is dismally low and significantly responsible for our food insecurity.

In conclusion, there is no doubt that the President and his team have done many things differently, such as the audacious simultaneous removal of the fuel subsidy and the unification of the multiple exchange rates, the floatation of the Naira, new fiscal and tax laws, the recapitalization of banks, and the minimum wage review.

These are comprehensive monetary, fiscal, and structural reforms that are delivering changes, transitioning our country from a restricted, inefficient, or crisis-prone economy to a more open, market-oriented, and competitive one. The pains uploaded upfront at the inception of the regime are giving way to discernible gains and unprecedented reset of the economy for sustainable growth and development. Our nation is poised to enter another era of pervasive economic boom, having emerged from the bust cycle that began in 2014 stronger.

A solid framework for replicating the economic boom of 2005 to 2014 has been laid by adopting market-determined exchange rates and fuel prices, and by ramping up crude oil production. The government must evolve pragmatic trade and investment policies to mitigate some of the unintended consequences of the reforms, such as dwindling household consumption, escalating inequalities, and the percentage of people living below the poverty line, while protecting local industries, attracting foreign investment, boosting job creation, and enhancing the standard of living of the people. Nigeria is no doubt set for another era of sustainable growth and development.

Dr Abolade Agbola, DBA, MSc Ag Econs, FCS, FCIB, Managing Director of Lam Agro Consult Limited and Lam Business Solutions, is a Stockbroker, Banker, and Agribusiness Business Consultant .He writes from Lagos

Economic reforms: How did President Tinubu uniquely reshape Nigeria’s economy?

Feature

Uranium, Sovereignty and the Sahel’s New Chains

Uranium, Sovereignty and the Sahel’s New Chains

By Oumarou Sanou

Sovereignty is not declared. It is exercised. And in today’s Niger, the uranium convoy rumbling toward Russia tells a story far removed from the revolutionary rhetoric echoing through Niamey.

The now-infamous “Madmax Uranium Express,” carrying 1,000 tons of Nigerien uranium to Russia, has been presented as proof of emancipation from Western domination. To its proponents, it symbolises a clean break from France and a reclaiming of national dignity. In reality, it exposes a far more uncomfortable truth: Niger has not escaped dependency—it has merely changed its custodian.

Russia is not “doing business” in Niger in any classical sense. Business implies choice, negotiation, competition, and mutual benefit. What is unfolding instead is extraction under constraint. By systematically isolating Niger and its partners in the Alliance of Sahel States (AES) from Western, regional, and multilateral partners, Moscow has cornered them into an exclusive and profoundly unequal bilateral relationship.

This is the modern face of neo-colonialism. Not flags or governors, but exclusivity. One dominant partner. No alternatives. No leverage.

True independence rests on multilateralism—the ability to balance partners against one another, to extract the best terms from each relationship, and to preserve freedom of action. Niger once practised this imperfectly but pragmatically. Under previous arrangements, uranium was sold to France at above-market prices, while political influence was diluted through diversified diplomatic and economic partnerships. The relationship was unequal, but Niger retained some room to manoeuvre.

That strategic balance has now collapsed.

Data recently published by EITI Niger (Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative) reveals the scale of the reversal. While global uranium prices have surged by more than 30 per cent since March 2025, Russia is purchasing Nigerien uranium at prices significantly below what France paid just two years earlier.

The figures are striking. In 2023, France paid approximately $275 million for 1,400 tons of uranium—about $196,500 per ton. In 2025, Russia is paying $170 million for 1,000 tons, or roughly $170,000 per ton. At current market rates, Niger could have earned well over $250 million for the same quantity.

What was once a strategic asset is now being discounted—sold cheaply to a new patron under the banner of sovereignty.

Sovereignty, however, cannot be sold off by the ton.

By accepting a below-market deal, Niger has surrendered not only revenue but leverage and dignity. The uranium shipped to Russia will power nuclear reactors for years, generating energy worth billions of dollars. Niger, meanwhile, receives a marginal fraction—barely enough to justify the long-term strategic cost of locking itself into a new dependency.

Even the symbolism of the transaction is revealing. The convoy itself was stalled for weeks, exposed to insecurity, insurgent threats, and logistical paralysis. It became an unintended metaphor for the AES project itself: loudly defiant, rhetorically sovereign, yet strategically immobilised.

General Abdourahamane Tiani insists, “Our uranium belongs to us.” Ownership, however, is meaningless without control over price, partners, and conditions. Selling under duress to a single power, especially one engaged in a prolonged and costly war, does not reflect autonomy. It reflects captivity.

The rhetoric may have changed, but the underlying logic remains the same. Niger has not dismantled unbalanced agreements; it has merely reoriented them. The exclusive links now forming between the Sahel States Alliance and Moscow risk creating the most severe relationship of subordination Africa has witnessed since independence—one defined not by development or technology transfer, but by extraction and political loyalty.

This is the great paradox of the current moment. In the name of sovereignty, Niger has narrowed its options. In the name of dignity, it has accepted a discount. In the name of independence, it has entered a relationship defined by dependency.

The Sahel does not need new masters. It needs options.

Absolute sovereignty lies in freedom of action—the ability to say yes, no, or renegotiate. It lies in multiple partnerships, competitive markets, and strategic ambiguity. It lies in refusing exclusivity, whether imposed by former colonial powers or embraced by new ones claiming anti-imperial credentials.

Until Niger and its neighbours reclaim the freedom to choose, negotiate, and diversify, sovereignty will remain a slogan rather than a lived reality. One can only hope that the Sahel will rediscover a simple but enduring truth: independence is not found in replacing one dependency with another—but in refusing dependency altogether.

Oumarou Sanou is a social critic, Pan-African observer and researcher focusing on governance, security, and political transitions in the Sahel. He writes on geopolitics, regional stability, and African leadership dynamics.

Contact: sanououmarou386@gmail.com

Uranium, Sovereignty and the Sahel’s New Chains

-

News2 years ago

News2 years agoRoger Federer’s Shock as DNA Results Reveal Myla and Charlene Are Not His Biological Children

-

Opinions4 years ago

Opinions4 years agoTHE PLIGHT OF FARIDA

-

News10 months ago

News10 months agoFAILED COUP IN BURKINA FASO: HOW TRAORÉ NARROWLY ESCAPED ASSASSINATION PLOT AMID FOREIGN INTERFERENCE CLAIMS

-

News2 years ago

News2 years agoEYN: Rev. Billi, Distortion of History, and The Living Tamarind Tree

-

Opinions4 years ago

Opinions4 years agoPOLICE CHARGE ROOMS, A MINTING PRESS

-

ACADEMICS2 years ago

ACADEMICS2 years agoA History of Biu” (2015) and The Lingering Bura-Pabir Question (1)

-

Columns2 years ago

Columns2 years agoArmy University Biu: There is certain interest, but certainly not from Borno.

-

Opinions2 years ago

Opinions2 years agoTinubu,Shettima: The epidemic of economic, insecurity in Nigeria